Betsy DeVos Wants to Give a Free Pass to the Student Loan Company That Ripped Off 78,000 Servicemembers

Last week, the Department of Education’s student lending arm radically changed the landscape of a planned billion-dollar contract in a move that tips the scales for Navient, one of the nation's largest student loan servicers.

By AUSTIN EVERS and SETH FROTMAN

Last week, the U.S. Department of Education’s student lending arm, the Office of Federal Student Aid, radically changed the landscape of its planned billion-dollar contract to reshape student loan servicing in a move that tips the scales for Navient, one of the nation’s largest student loan servicers.

By altering one sentence buried deep in thousands of pages of contract requirements, Secretary Betsy DeVos and her team gave the world a glimpse of the corruption at the core of our $1.5 trillion student loan market.

When applying for these government contracts, student loan servicers are required to disclose past violations of consumer protection laws. But now the government has shortened the disclosure period to just the past five years, giving the embattled student loan giant a free pass on one of the biggest scandals to hit the student loan industry in the past decade — a scheme by Navient to cheat 78,000 servicemembers out of more than $60 million.

How did Navient rip off so many servicemembers?

The Servicemember Civil Relief Act entitles active-duty members of the military to reduce the interest charged on certain financial products to 6 percent—a statutory cap that applies to both private and federal student loans. But in 2011 and 2012, active-duty servicemembers across the country told the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau that student loan companies had imposed extra, unnecessary paperwork requirements and that the companies’ staff provided military borrowers with incorrect information about their rights and benefits.

CFPB’s Office of Servicemember Affairs and its Student Loan Ombudsman published a report chronicling these abuses. At the same time, the CFPB referred complaints by military borrowers about Navient to the Department of Justice and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), both of which opened investigations.

In 2014, just after it had completed its spin-off from Sallie Mae, Navient settled with federal officials, pledging to return $60 million to 78,000 servicemembers. As the Department of Justice described when announcing the settlement, the scope of these abuses stretched across Navient’s operations:

The proposed settlement covers the entire portfolio of student loans serviced by, or on behalf of, [Navient]. This includes private student loans, direct Department of Education loans and student loans that originated under the Federal Family Education Loan Program. The proposed settlement is far-reaching, with certain sevicemembers to be compensated for violations of the SCRA that occurred almost a decade ago.

On the same day, the FDIC announced a settlement for a range of other abuses by Navient and Sallie Mae, including unfairly processing borrowers’ payments to harvest extra late fees and deceiving borrowers about the company’s late-fee policies. The FDIC also settled with Sallie Mae for violating the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, a federal fair lending law intended to prevent discrimination by financial services companies. In addition to the $60 million returned to servicemembers, the FDIC’s action returned another $30 million to other borrowers.

What does this mean for Navient’s contract with the government?

Despite significant scrutiny by Congress, including years of continued pressure from Senator Elizabeth Warren, the Department of Education never held Navient accountable for these abuses. In fact, Navient remains a contender for a new student loan servicing contract potentially worth as much as $1 billion over the next decade.

That is why these recent revelations are outrageous.

For four years, in fits and starts, the Office of Federal Student Aid (FSA) has sought to redesign the contracts it uses to outsource student loan servicing to the private sector — a procurement now known as “NextGen.” These contracts are big business, driving hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue to private-sector firms like Navient when they win an award.

Given the long and sordid history of abuse across the student loan industry, law enforcement officials and Congress have pressed FSA to consider vendors’ history of illegal practices during the procurement process. In a letter she co-authored with 25 other senators in December, Senator Patty Murray, ranking member of the Health Education Labor and Pensions Committee, explained, “In recent legislation funding the Department, Congress has directed the agency to evaluate NextGen contractors’ ‘history of compliance’ with consumer protection laws, and that this system must ‘incentivize more support to borrowers at risk of being distressed.'”

In response, FSA required potential vendors to disclose their past history of “consumer protection compliance.” If taken at face value, this process meant that, at long last, the Department of Education would finally consider Navient’s history of abuses when the government determines who will receive its lucrative servicing contract in the future.

Evaluating Navient’s past abuses is critically important for millions of Americans with student debt because, too often, past is prologue. A wave of pending lawsuits suggests this is true in Navient’s case — state attorneys general and the CFPB have alleged Navient “fail[ed] borrowers at every stage of repayment,” including by “harm[ing] the credit of disabled borrowers, including severely injured veterans,” and breaking a range of federal and state laws in the process.

What changed last week?

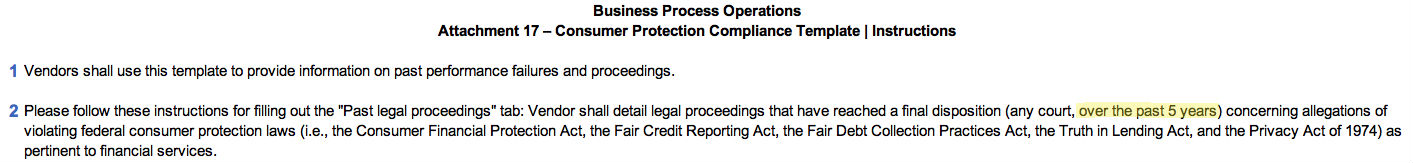

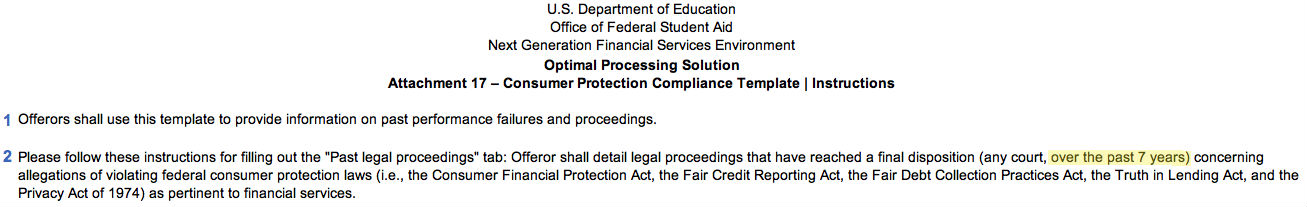

Last week, FSA issued an amendment to its ongoing procurement, quietly changing a single term buried deep in a spreadsheet that provides guidance to potential vendors. Through this action, it told prospective vendors they only needed to disclose five years of history related to past violations of consumer protection laws.

Previously, the government expected seven years of disclosures.

This change may seem small, but its effect is enormous — because Navient’s settlement in the lawsuit on behalf of servicemembers happens to have taken place five years and one month ago.

Now, Navient no longer needs to disclose — and the government can no longer consider — enforcement actions that document Navient’s full history of wrongdoing. Because these actions took place just barely outside of the new reporting window dictated by FSA, Navient can certify to the government that it has a clean past, and FSA can ignore abuses that cost our men and women in uniform tens of millions of dollars. DeVos and her team appear to have chosen a time frame that, by a single, miraculous month, grants Navient a clean slate and whitewashes the experiences of 78,000 men and women who bravely served our nation.

Demanding answers from the Department of Education

Today, we are demanding answers from the Department of Education about how this decision was made, who was involved in the decision-making process, and whether Navient’s army of lobbyists and lawyers exerted improper influence over this billion-dollar decision. Student loan borrowers — and all Americans — deserve the to know the truth.

Austin Evers is the Executive Director of American Oversight, a non-partisan, nonprofit ethics watchdog and the top Freedom of Information Act litigator investigating the Trump administration. Since its launch in March 2017, American Oversight has filed more than 100 public records lawsuits, uncovering and publishing tens of thousands of documents including senior officials’ calendars, emails, and expense records.

Seth Frotman is the Executive Director of the Student Borrower Protection Center. He previously served as Assistant Director and Student Loan Ombudsman at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, where he led a government-wide effort to crack down on abuses by the student loan industry and protect borrowers.