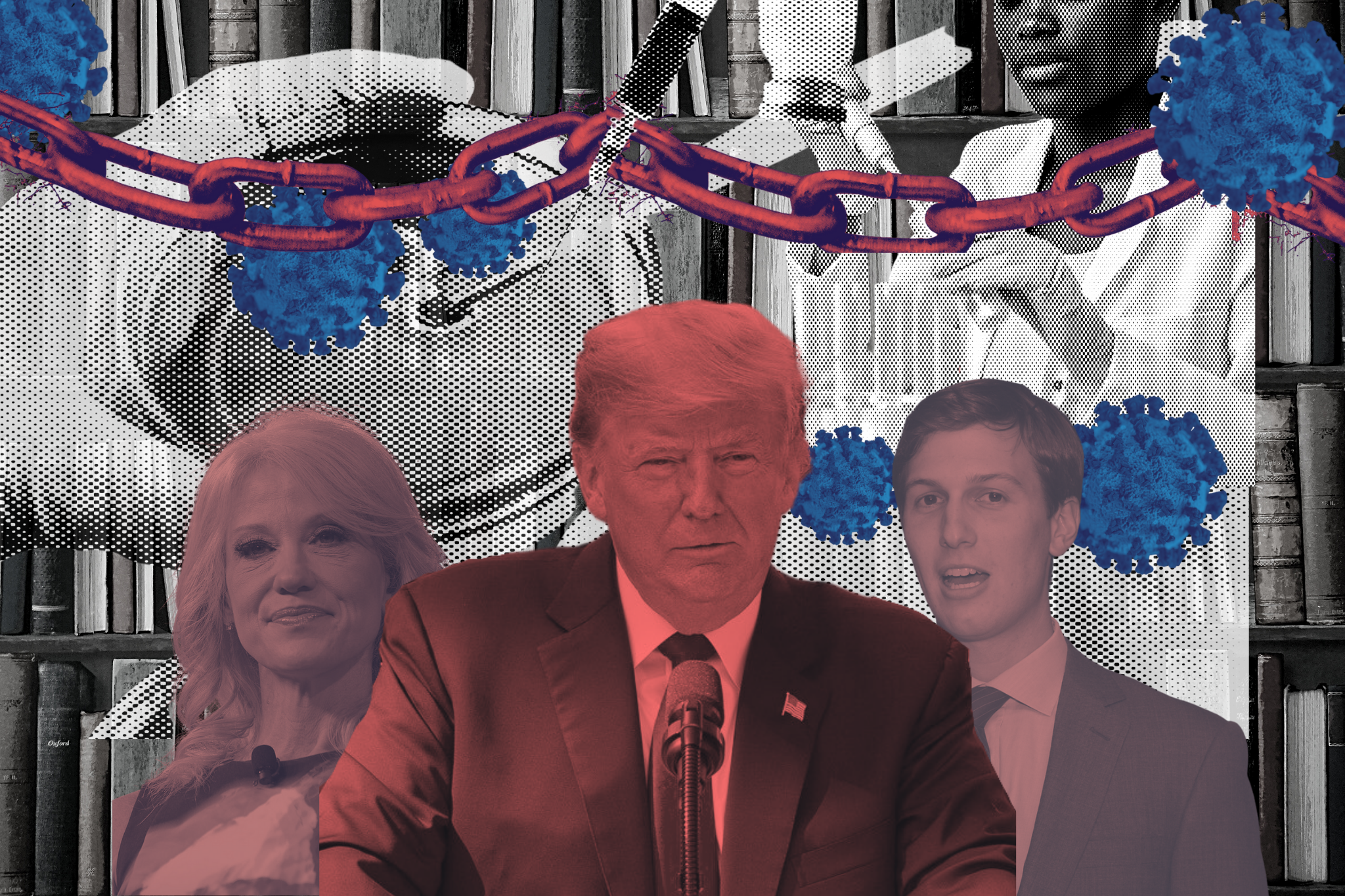

Documents from March and April Reveal Cozy White House Private-Sector Communications About Pandemic

Documents recently obtained by American Oversight add further color to reports of private individuals and groups — some with ties to the president — being granted privileged access to propose pandemic actions.

During the early months of the Trump administration’s floundering response to the coronavirus pandemic, officials — including the president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner — relied on private companies to address supply shortages and other challenges, often resulting in coordination problems and, in some cases, duplication of federal efforts. During this time, private individuals and groups, some with ties to the president, were granted privileged access to propose solutions.

Documents recently obtained by American Oversight add further color to these reports, suggesting that private-sector representatives had easy access to White House officials and were able to get their feet in the door, seemingly without going through more formal channels.

On March 18, an individual from the Gula Graham political consulting group emailed Jeffrey Freeland, a special assistant to the president, and Steve Pinkos, a senior adviser to the president, about Orb Health, a telehealth company. The individual emphasized that Orb Health’s telehealth network and at-home testing kits would produce “LOTS of wins for the President.”

Pinkos directed the individual to send the information to Joseph Grogan, former Domestic Policy Council director, who asked for more details on what was being proposed. “And the ask is?” Grogan wrote. “You need Medicare to contract with them to do this? Or some other part of HHS? Or do you want us to educate private payers that this service exists so they can save money by keeping patients and clients out of the hospital?” The individual replied that Orb Health was requesting HHS funding, and Grogan forwarded the email to Brady Brookes, the chief of staff at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. It’s unclear whether the company received money.

On April 10, Kellyanne Conway, who was then a counselor to the president, forwarded an email about Ziegler, a private investment bank, from her personal account to her government account. Part of the email’s subject line was “Hope you are well,” suggesting a personal connection with the redacted sender, who went on to reference a partner’s work in telemedicine and to offer an introduction to an analytics company called Socially Determined that had been “spending time with HHS and state governments to plan for the post-pandemic recovery and needed supportive services and funding.”

In another exchange from late March, top Trump donor Henry Kravis, whose name Trump had reportedly floated for Treasury secretary, appears to have leveraged his White House ties to receive government assistance for his business. On March 26, Kravis, co-founder of the private equity firm KKR, emailed Chris Liddell, the deputy chief of staff for policy coordination at the White House. Kravis said that Envision, a health care company that KKR acquired in 2018, “does all of our billing for the health work we do in the US.” This work was primarily done in India, and Envision was struggling to complete it due to pandemic-related shutdowns in India. He continued, “If we can’t resolve this quickly, the company will run out of money.”

According to the email, Kravis asked that Liddell speak with the CEO of Envision. Liddell forwarded the email to Deputy National Security Adviser Matt Pottinger, who looped in Ken Juster, the ambassador to India, HHS Secretary Alex Azar, National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien, and White House pandemic task force leader Deborah Birx, and then shared the contact information for Envision Health’s CEO with an individual whose name is redacted. In June, Bloomberg News reported that almost 300 entities affiliated with Envision had received millions of dollars in HHS loans.

The records also include some of Kushner’s communications with private companies in March, when he had attempted to take charge of national testing efforts. On March 27, a Walgreens representative sent an email to Kushner with draft language that “was developed for Secretary Azar to use regulatory authority” that would allow pharmacists to administer coronavirus tests. A few days later, on March 31, a Walgreens representative again emailed Kushner, saying that Walgreens had worked with the American Medical Association to soften AMA’s position on pharmacists conducting coronavirus tests, and asking that the White House support a legislative provision that would allow for it (in April, HHS issued guidance authorizing pharmacists to administer tests).

On April 2, Grogan emailed an individual at Cepheid, a diagnostics company that created the Xpert Xpress Coronavirus test, saying, “Let me know when you can connect.” The contact from Cepheid then sent a proposal about C360, a database for testing data, and asked for an endorsement from the White House Coronavirus Task Force.

On April 13, an employee of Deerfield Management Company, a health care investment firm, emailed Food and Drug Administration chief Stephen Hahn saying, “I am working to get you more visual material for your discussion.” The employee referenced a “wellness app … to answer important questions about the epidemic.”

In addition to these communications, this set of documents includes exchanges and meetings between White House officials and health agency officials. You can read more about these records here.