As Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis comes under fire for his potentially favoritism-laced approach to vaccine distribution, American Oversight has obtained thousands of pages of documents from the Florida Department of Health that shed light on the state’s pandemic response last spring. These documents show early data-gathering and testing difficulties, including disagreements between Florida health officials and officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As cases of Covid-19 continued to emerge in the United States in February 2020, the records show that for at least a month Florida officials resisted using the CDC’s system to track Covid-19 data.

According to the documents, CDC officials requested on Feb. 6, 2020 that Florida officials start using their system for data collection, called DCIPHER. The CDC followed up with Florida repeatedly, asking state officials on Feb. 12 and Feb. 15 to designate staff to manage the Covid-19 data. Florida officials replied, “Per previous conversations, we will not be using DCIPHER.”

The documents suggest that the DCIPHER system, which Florida apparently resisted using, was being used by other states at the time — in slides attached to a Feb. 19 email, the CDC said it was using DCIPHER to track Covid-19 cases and that “most jurisdictions” had reported at least two users. (Public reporting later indicated that DCIPHER faced difficulties in keeping up with coronavirus data.)

On March 9, the CDC contacted Florida officials again, writing to Florida epidemiologist Carina Blackmore, “We wanted to reach out to you personally, though, because we did not receive confirmation of Florida’s case counts for Monday’s web update.” On the same day, José Montero, director of the CDC Center for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Support, reached out to Florida Surgeon General Dr. Scott Rivkees. Montero said he wanted to “bring back to your attention our request for your participation on syndromic surveillance” and described the multiple times the issue had come up.

Later communications in these documents suggest that Florida may have eventually agreed to use DCIPHER. But the first week of March saw Florida’s first Covid-19 cases and deaths, when officials were still apparently failing to report data to the CDC through DCIPHER. By March 16, more than one-third of Florida counties had reported Covid-19 cases.

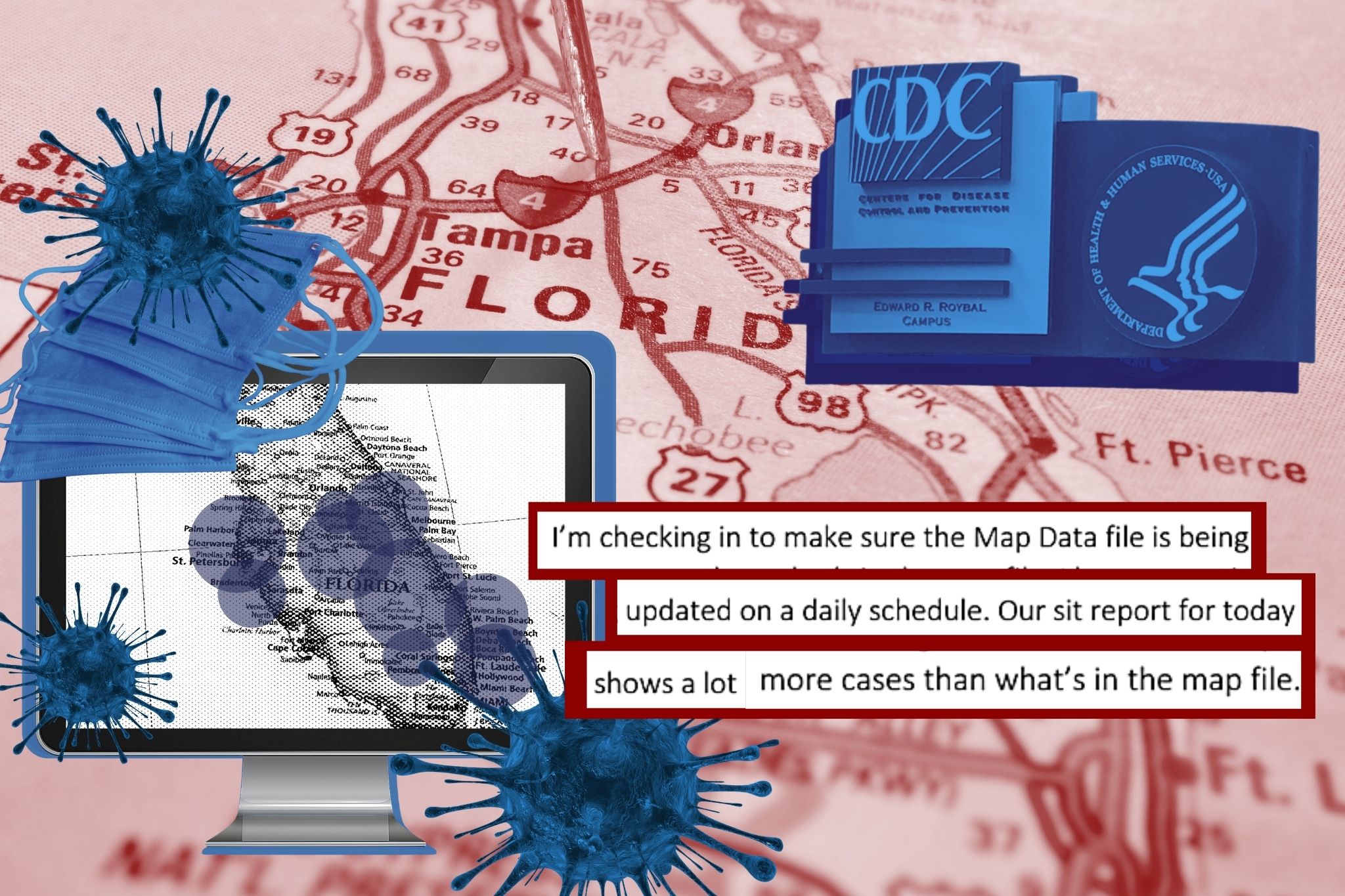

The documents also include communications from Rebekah Jones, the Florida Department of Health data scientist who said she was fired in May 2020 for refusing to change coronavirus data to support DeSantis’ early reopening plan. On Dec. 9, 2020, armed police raided her home, which Jones said was due to her public critiques of DeSantis.

On March 14, 2020, according to the records, Jones wrote to colleagues about Florida’s map of Covid-19 cases. Jones expressed concern that the map showed fewer cases than that day’s situation report, so she proposed having the map update more regularly throughout the day. She followed up an hour and a half later, describing a discrepancy between the Johns Hopkins University map and Florida’s own — according to her, the gap was likely because the Johns Hopkins map was updating directly from the CDC and there may have been some discrepancy about “repatriated cases,” in reference to U.S. citizens who were brought to Florida with federal assistance after traveling abroad.

In the months after, Florida officials repeatedly obfuscated data. DeSantis refused to publish the White House Coronavirus Task Force’s Florida reports, which newspapers argued had public value. When the Center for Public Integrity finally released the reports, they showed the task force had urged state leaders to increase mitigation efforts at the same time DeSantis was publicly saying there was no need for business restrictions.

Finally, the documents show that on March 11, epidemiology field officer Ann Schmitz responded to a query from a health official asking colleagues whether they had received guidance about testing asymptomatic individuals. Schmitz said that the health department was “not recommending testing of asymptomatic persons, though as you are aware a handful of exceptions were made for the cruise industry.” Testing of asymptomatic persons is crucial to map the reach of the virus, as asymptomatic transmission can enable wider community spread. At the time of Schmitz’s communication, it was public knowledge that there was community spread of the coronavirus in Florida — something DeSantis had downplayed.

We also received communications indicating that Florida and CDC health officials as well as the cruise industry faced confusion in repatriating those who had been on cruise ships when the pandemic began to take hold. Records of these communications can be found here and here.