Health Care Lawsuit: Fighting for Transparency

American Oversight filed a new motion opposing efforts by the Trump administration and Congress to block the release of emails detailing the secret health care reform negotiations.

American Oversight files Motion Opposing Efforts by Trump Administration and Congress to Block Release of Obamacare Repeal Emails

American Oversight is taking on both the Trump administration and Congress in our fight to bring transparency to the health care reform process – and on Tuesday we filed a new brief in our lawsuit arguing that the public has a clear right to see the records of the Obamacare repeal negotiations between Capitol Hill and the administration.

In Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) cases, we’re typically up against the administration arguing that it shouldn’t have to release information to the public. That’s happening here, too, but in this case we’re also facing a separate challenge from Congress making its own arguments about why certain health care related emails should be hidden from public view.

More troubling – in fighting to conceal these health care documents, both the Trump administration and Congress have made sweeping, ill-conceived arguments that could severely limit government transparency across the board and undermine the Freedom of Information Act.

Statement from Austin Evers, Executive Director of American Oversight.

“With the health care of millions of Americans at stake, the public has a right to know what our leaders were really saying to each other about health care reform. It is deeply disappointing that Congress and the Trump administration are so desperate to keep their Obamacare repeal negotiations secret that they’re willing to roll back fundamental transparency protections.”

Overview:

On May 25, 2017, a federal judge ordered the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to release records of their communications with Congress regarding health care reform legislation.

American Oversight had previously sued the two agencies for failing to respond to FOIA requests for the records. Lies are a form of corruption, and we wanted to find out if the public talking points on health care lined up with the private negotiations happening behind closed doors.

The administration complied with the court order, but it blacked out every single substantive exchange, including emails between OMB Director Mulvaney and House Speaker Paul Ryan. Those documents can be found here.

The Trump administration is arguing that it is allowed to redact the contents of its emails with Congress under FOIA exemption (b)(5) which permits agencies to withhold internal agency deliberations, which some courts have extended to communications with “outside consultants.”

This argument is problematic for a number of reasons:

- First, the exemption the agencies rely on protects “inter-agency or intra-agency” communications but, under the FOIA statute, Congress is not an “agency.”

- Second, Congress cannot be a “consultant” for the executive branch, particularly where, as in 2017 surrounding health care, its interests diverge from the agencies. Agencies can hire consultants, but those consultants operate as de facto agency employees. By no stretch of the imagination could Congress be said to fill that role here.

- Third, the so-called “common interest” privilege has never been applied to, and does not apply to, agency deliberations, much less negotiations between independent branches of government.

- Fourth, treating Congress – a separate, co-equal branch of government – as a consultant distorts our system of constitutional government. James Madison would roll over in his grave if he heard the government’s position.

- Finally, the ramifications of endorsing this argument would be dire and unprecedented, potentially sweeping huge swaths of material into obscurity, harming transparency, and undermining accountable government. The government’s arguments could apply not just to Congress but also to Exxon Mobil and the Chamber of Commerce.

But that’s not the only argument we’re up against. Congress filed a separate motion to intervene in this lawsuit, arguing that four specific email chains are “congressional records” rather than “agency records” and should not be subject to FOIA.

Congress bases its argument on the fact that some messages within these chains include footers – form text appended to a signature block – declaring that those emails should be considered congressional records.

Congress exempted itself from FOIA, but there has never been a case that endorses this approach or one that involves such routine, ad hoc, back-and-forth communications between the independent branches of government. If Congress wins this argument, we can expect congressional staffers to use this kind of footer language all the time as a quick way to avoid public scrutiny, and it could cover a wide range of agency documents even where the agency is performing ordinary agency functions, not just assisting Congress.

American Oversight’s lawyers have marshaled the law and logic to fight these claims. Both are on our side. But ultimately, as we face off against two branches of government, the responsibility for protecting the FOIA statute and the constitutional separation of powers lies in the third. We are hopeful that the court will come down in our favor.

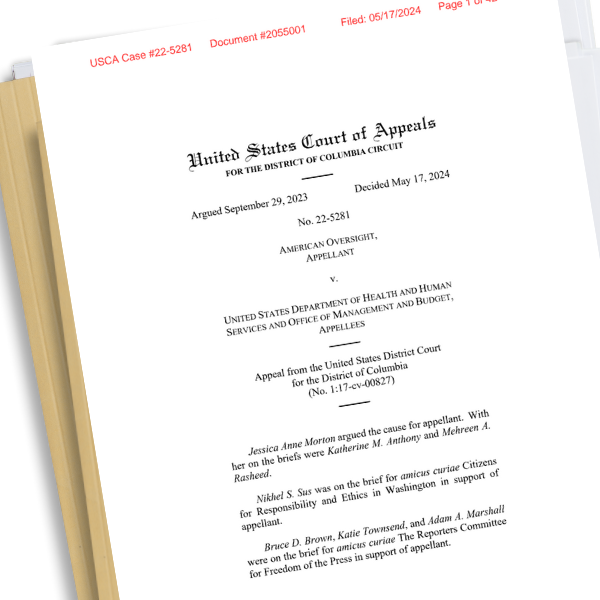

American Oversight’s brief can be viewed and downloaded here.

A more detailed explanation of the case and the issues involved can be found below.

I. Background:

The case involves FOIA requests we filed earlier this year asking for communications between HHS or OMB and Congress over health care reform. Our theory was that the behind-the-scenes dialogue wouldn’t match the talking points congressional and administration officials were spinning to the public, and we wanted to expose that. We also had a legal rationale behind what we did: under FOIA, agencies like HHS and OMB generally can’t withhold communications they have with people outside the executive branch. Agencies can have private internal conversations but they lose the cone of protection when they engage outsiders. It’s a principle that, among other things, allows the public to see what outside lobbyists and influencers are saying to our public officials.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the administration took extraordinary steps to block our efforts. While the agencies were forced to comply with a court order requiring them to turn over documents by early September, the thousands of pages they produced were covered in big, black redaction boxes. The documents confirmed our gut instinct that the administration was having significant discussions over email with its friends in Congress, but the redactions obscured every single substantive exchange (except for Paul Ryan’s emojis).

The redactions flew in the fact of the principle that the agencies’ external communications generally can’t be redacted under the FOIA. And as laid out below, the redactions also represent an incursion against the constitutional separation of powers, seeking to create a special exception for the Framers’ design when one party controls both Congress and the White House.

But before we get there, we have to introduce another, unexpected adversary. Despite the aggressive redactions on the documents, it turns out Congress didn’t think the administration went far enough. Four email chains among the hundreds of pages included a generic footer, inserted by some mechanism by congressional staffers, stating that the messages and “related” documents were “congressional records” and were not subject to FOIA. In September, the House Ways & Means Committee intervened in our lawsuit to argue that those four email chains should not have been turned over in any form; they should have been entirely invisible to the public.

In short, the administration is arguing that it can redact every substantive exchange in these emails despite the fact that they are communications with Congress that are normally subject to disclosure, and the Committee is arguing that the public shouldn’t even know that some of those emails exist.

Which brings us to today and American Oversight’s legal brief fighting these extraordinary anti-transparency efforts.

II. The Legal Fight—and the Important Stakes

The most important thing to understand about the arguments the administration and Congress are making is they are almost unprecedented and, if successful, would strike major blows against the public’s right to know what its government is up to. If either wins its argument, huge swaths of information that could otherwise be made public would be condemned to obscurity, for the very first time. Transparency is one of the only tools the public has to prevent, expose, and punish corruption. This is not the time to restrict it.

To understand why this is the case, let’s walk through the arguments being proffered and our rebuttals to them, starting with the agency arguments and then turning to Congress’s arguments.

A. The administration is treating one-party rule as a rationale to gut the separation of powers and invent new anti-transparency exceptions.

Under FOIA, agencies may withhold from the public “inter-agency or intra-agency memorandums or letters that would not be available by law to a party other than an agency in litigation with the agency . . . .” In plain English, agencies don’t have to disclose deliberations that occur within agencies or between agencies because doing so would chill those deliberations from taking place. For example, debates within HHS over what health care policy to enact generally can be redacted as “intra-agency” deliberations, whereas HHS’s emails with, say, an outside policy advocacy group about health care cannot.

Importantly, Congress is not an “agency” under FOIA. Congress wrote the statute and very explicitly exempted itself from the definition. But if Congress isn’t an “agency,” how can communications between agency personnel and congressional staff be protected as “inter-agency or intra-agency?” The answer under the statute is clear—they can’t—or at least that should be the case.

Here, the agencies have put forward two novel arguments. First, they argue that in the context of health care reform, Congress was serving as a “consultant” to the agencies, thereby bringing communications within the cone of protection. Second, they argue that the interests of the agencies and Congress were so aligned on health care that they can be protected under a “common interest” theory of privilege.

We disagree for several reasons.

First, as noted above, Congress isn’t an “agency” so its communications are not “inter-agency or intra-agency.” For the textualism legal minds out there, when the statutory text is unambiguous, the analysis should end.

Second, Congress is not, and cannot be, a “consultant” to executive branch agencies. While there is a line of cases that discuss the role of consultants under FOIA, none involves a case like this where the purported “consultant” had its own interests and was not effectively standing in the shoes of normal agency employees. You can’t look at the health care debate and think Congress was either unified within itself or acting on behalf of the administration. Ask the Freedom Caucus and the Republican Study Committee whether they were on the same team with each other or with the administration at any given time this year. Indeed, in this very case Congress has intervened in the litigation to assert that it was not working on behalf of the agencies on health care, quite the opposite (see part II.B below).

Third, the “common interest” privilege asserted by the government literally has no application in this context. That privilege was developed to allow lawyers for parties engaged in the same legal matter, like litigation, to share information without waiving the attorney client privilege. It has never been applied to discussions between separate branches of government. It’s simply inapposite.

Fourth, the government’s position fundamentally misunderstands and distorts our constitutional scheme. The Constitution establishes a system of separation of powers under which each branch is separate, co-equal, and adverse to the others. As James Madison wrote in Federalist 51, the Constitution is designed to let “[a]ambition . . . counteract ambition” by giving each branch “the necessary constitutional means, and personal motives, to resist encroachments of the others.” The notion that the executive branch could engage Congress as a consultant or that it can assert a “common interest” with Congress shatters the very framework of our system. The separation of powers is not meant to be convenient, quite the opposite. Madison did make an exception for when the separation of powers would be unnecessary: when humans are “angels.” Notably, the government has not claimed divine status in its briefs.

Finally, the consequences of endorsing either of the government’s arguments would be dire. Congress enacted FOIA 50 years ago to promote transparency. As the Supreme Court said, “The basic purpose of [ ] FOIA is to ensure an informed citizenry, vital to the functioning of a democratic society, needed to check against corruption and to hold the governors accountable to the governed.” NLRB v. Robbins Tire & Rubber Co., 437 U.S. 214, 242 (1978). Up until now, communications between agencies and outside entities have been subject to that disclosure. But if the government wins on either of its theories, not only would communications with Congress be hidden from view, it could lead to many other external communications being obscured. For example, should the EPA be allowed to withhold its communications with conservative groups this year because it shares their views? The same standard wouldn’t apply to adversarial groups, such as environmental groups. If an election changed who is in power, the rules would flip.

B. Congress does not own its negotiations with the executive branch

Congress has intervened to challenge the release of four email chains in which some, but not all, messages are marked with a generic footer that the messages and “related” documents are “congressional records” and not subject to FOIA. That’s wrong; the documents are “agency records” under FOIA.

Citizens can use FOIA to reach “agency records.” Put simply, a document is an “agency record” if it was created or obtained by an agency and where the agency has control over the document, relies on the document, and integrates it into its files. The emails here plainly qualify: all of them were drafted or obtained by agency personnel and, according to the government’s arguments, relied on by the agency to formulate agency policy.

Congress would like the documents to be categorized as “congressional records,” which are exempt from FOIA. To qualify, courts require that Congress express a clear, particularized intent to retain control over the documents in question. The footer on the emails in this case does not meet that standard: it is an imprecise, generalized, and generic stamp inserted on ad hoc, routine inter-branch correspondence based on the subjective views of a congressional staffer.

In addition, there is no evidence that the agencies ever agreed to be bound by these footers; indeed, to some uproar earlier this year, the DOJ clarified that the executive branch can only be bound by the House, Senate, or chairs of congressional committees, not individual members (or, by corollary, individual committee staffers). Thus, it appears that Congress is trying to deny the public access to information based on instructions it tried to impose on the executive branch without prior agreement.

There has never been a case in which courts have protected the routine back-and-forth email exchanges pertaining to the independent tasks of the Congress and executive branch. In contrast, the quintessential congressional record case involved a transcript of confidential congressional testimony sent to an agency with express instructions that it could be used only for limited purposes.

In addition to being legally incorrect, Congress’s argument, if successful, would have serious, pernicious ramifications. Here’s why: there is nothing about the marked email messages that distinguishes them in substance from any of the other hundreds of pages of material—except that footer. And if the generic footer alone is sufficient—without regard to the content or nature of the underlying document—then the only reason Congress isn’t challenging the rest of the emails is that no one remembered to insert the footer.

Put another way, if the Committee wins, nothing would stop any of the thousands of congressional staffers on the Hill from taking it upon themselves to mark any of their emails with agencies as “congressional,” overriding the entire statutory scheme of FOIA. Seriously: if the footer is sufficient, anything from invitations for coffee to requests on behalf of well-heeled donors could be cloaked in invisibility on the mere say so (or, as our brief puts it, ipse dixit position) of a random Hill staffer.

In addition, there is no evidence that the agencies ever agreed to be bound by these footers; indeed, to some uproar earlier this year, the DOJ clarified that the executive branch can only be bound by the House, Senate, or chairs of congressional committees, not individual members (or, by corollary, individual committee staffers). Thus, it appears that Congress is trying to deny the public access to information based on instructions it tried to impose on the executive branch without prior agreement.

There has never been a case in which courts have protected the routine back-and-forth email exchanges pertaining to the independent tasks of the Congress and executive branch. In contrast, the quintessential congressional record case involved a transcript of confidential congressional testimony sent to an agency with express instructions that it could be used only for limited purposes.

In addition to being legally incorrect, Congress’s argument, if successful, would have serious, pernicious ramifications. Here’s why: there is nothing about the marked email messages that distinguishes them in substance from any of the other hundreds of pages of material—except that footer. And if the generic footer alone is sufficient—without regard to the content or nature of the underlying document—then the only reason Congress isn’t challenging the rest of the emails is that no one remembered to insert the footer.

Put another way, if the Committee wins, nothing would stop any of the thousands of congressional staffers on the Hill from taking it upon themselves to mark any of their emails with agencies as “congressional,” overriding the entire statutory scheme of FOIA. Seriously: if the footer is sufficient, anything from invitations for coffee to requests on behalf of well-heeled donors could be cloaked in invisibility on the mere say so (or, as our brief puts it, ipse dixit position) of a random Hill staffer.

Conclusion

At one point, the agencies argue that they should be allowed to withhold communications with Congress because they are “controlled by the same political party.” That says it all: in what should be a standard FOIA case, we are facing the dangerous argument that the powerful can discard our system of checks and balances and the rule of law when politically convenient. That’s not how it is supposed to work. It’s not how the Constitution was designed and it’s not how the FOIA statute was drafted. With two branches of government aligned against transparency, we are counting on the third to step in to protect the public. We look forward to addressing the court in November.