Conservative Efforts to Sabotage Ballot Initiatives

In the wake of the overturning of Roe v. Wade, people across the country have gathered signatures in support of ballot initiatives that would ensure access to abortion. In response, state legislators, public officials and anti-choice groups have taken aim at these citizen-led examples of direct democracy.

Ballot initiatives are an important tool that allow citizens to participate in direct democracy by giving voters the ability to effect change when the public disagrees with the stance — or inaction — of their elected officials.

In more than half of all U.S. states, people can place measures on the ballot and pass the statutes or constitutional amendments through the popular vote. While the process varies in each state, such campaigns generally must collect a certain number of signatures to get an initiative on the ballot. If enough of the public votes “yes” on the proposal during an election — in some states it is a simple majority of voters, but other states require higher thresholds — it passes.

Citizen initiatives have a long history as a form of direct democracy and have been used to pass laws addressing a wide range of issues. But the process has come under attack in response to a growing number of states having proposed — and in several states, passed — ballot measures to protect abortion rights in the wake of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade in 2022, in some cases overriding state laws that limit reproductive rights.

Attacks on Direct Democracy

Since 2022, Americans in seven states — California, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Montana, Ohio, and Vermont — have voted to protect abortion rights through ballot initiatives.

Efforts to undermine the will of the voters have continued even after those measures have passed. American Oversight obtained records from the Ohio Attorney General’s office which included a memo specifically searching for ways to sabotage the state’s recently passed ballot measure, titled “Purpose: To identify what sections of the Human Rights and Heartbeat Protection Act … can be legitimately defended after the passage of the new Reproductive Rights Amendment to the Ohio Constitution.” In the document, the unknown author specifically advocated that the fetal heartbeat provisions of the Ohio Code could still be used, even after the ballot measure passed.

In other states, ballot measures have faced tests in courts, even after passage. In July 2024, the Kansas Supreme Court struck down two anti-abortion laws, affirming the right to an abortion in the state constitution created by the 2022 ballot initiative.

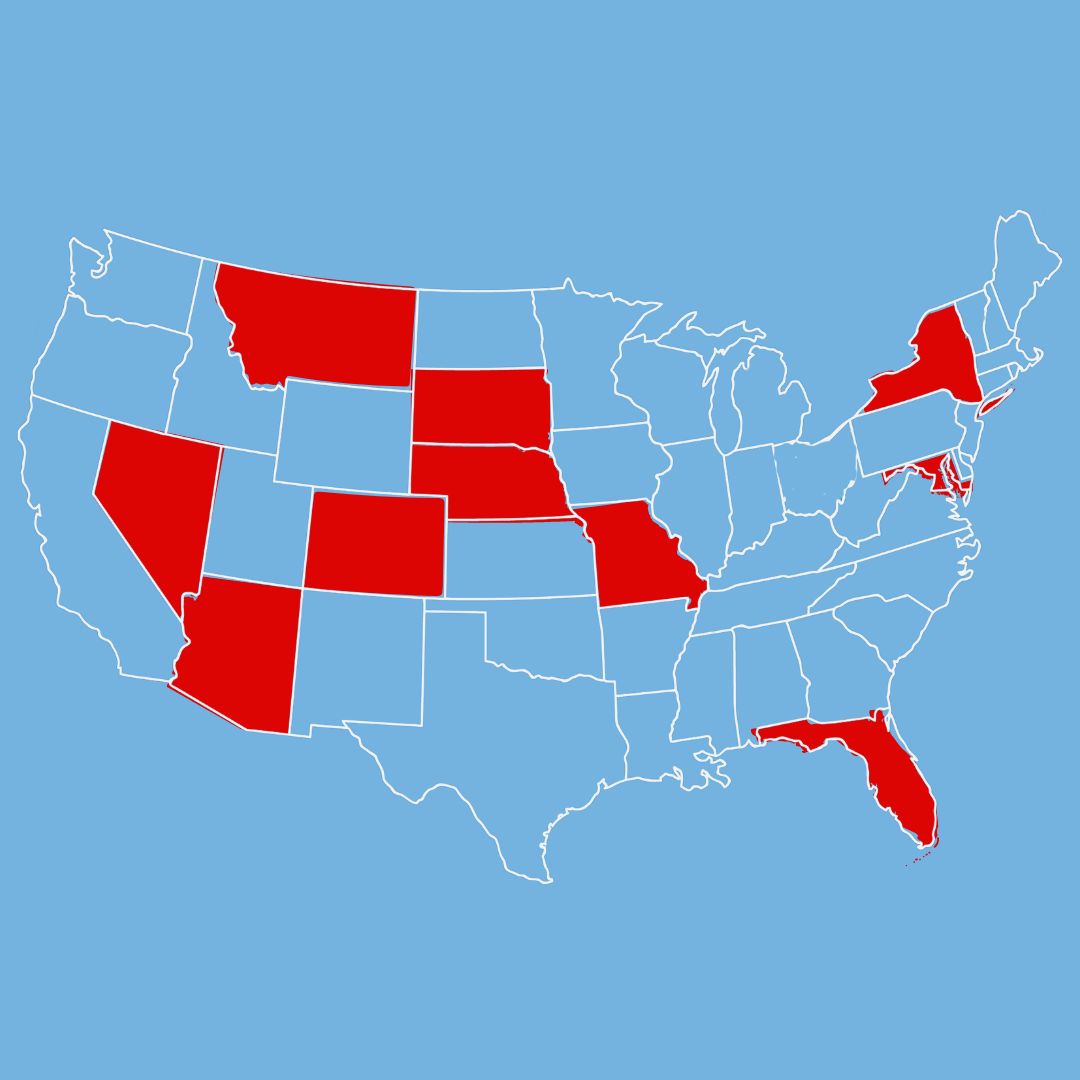

In 2024’s November election, voters in 10 states will have initiatives related to abortion rights on their ballots: Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New York, and South Dakota — a record number for a single election.

Legislators and anti-abortion groups are using a variety of tactics to limit the success of ballot initiatives.

Legislators and anti-abortion groups are using a variety of tactics to limit the success of ballot initiatives.

This year in Mississippi, for example, the state House passed a measure that would have revived the state’s dormant ballot initiative process — but also barred initiatives related to abortion on the statewide ballot. (Ultimately, this did not become law.)

In South Dakota, the anti-abortion group Life Defense Fund sued to keep the abortion rights citizen initiative off the November 2024 ballot, claiming the sponsor of the initiative failed to prove that its canvassers were all South Dakota residents. A judge dismissed the lawsuit in July.

A week after the June 2024 deadline for ballot initiative signatures in Montana, Secretary of State Christi Jacobsen instructed counties not to count the signatures of inactive voters. Two organizations that gathered signatures for the measure have sued, arguing that county officials had previously accepted the signatures of inactive voters. In July, a judge ruled that the inactive voters’ signatures should be counted and gave county election offices additional time to tally the signatures.

In Florida, Republican officials drafted a financial statement to accompany the November 2024 abortion rights ballot measure. The statement does not give a monetary amount for the measure’s cost, but it argues that its passage would lead to fewer births, which would hurt the state’s growth and revenue over time. Additionally, the financial statement speculated that the measure’s passage would result in expensive litigation. Abortion rights groups have filed lawsuits in an attempt to prevent this language from appearing on the ballot.

In Arkansas, an anti-abortion rights group published the identities of canvassers paid for their work gathering signatures for the abortion rights ballot initiative. Groups gathering signatures called this an intimidation tactic. The supporters of the initiative submitted more than 101,000 signatures — more than the 87,382 required — but the Arkansas secretary of state rejected the petitions, claiming the group did not submit required statements regarding paid canvassers. Abortion-rights group Arkansans for Limited Government filed a lawsuit seeking to reverse this decision in July. In August, the Arkansas Supreme Court upheld the secretary of state’s rejection of the signatures, ensuring the measure would not appear on the November 2024 ballot.

In July, Arizona Right to Life filed a lawsuit to disqualify a proposed ballot initiative that would overturn the state’s current 15-week abortion ban. The group claimed canvassers made misleading claims about the initiative and challenged the validity of some signatures. The group has since dropped one part of its lawsuit but maintains the measure is “inherently misleading.”

On Aug. 13, the Missouri secretary of state’s office certified that the ballot measure qualified to appear on the ballot for the November election. Less than 10 days later, an anti-abortion activist and two Missouri lawmakers filed a lawsuit to block the amendment from the ballot, alleging that the measure violates the state constitution because it does not specify the statutes that would be overturned if the amendment passes. Additionally, the lawsuit claims the measure violates a requirement that laws deal with only one subject. In September, a judge ruled in favor of the anti-abortion rights individuals and Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft decertified the ballot measure. The state Supreme Court ruled the measure could remain on the ballot just hours before ballots were to be finalized.

Records we previously obtained from Sen. Mary Elizabeth Coleman, one of the state legislators that brought the lawsuit, highlight her anti-abortion views. When asked by a reporter about a letter to the editor that claimed Coleman was “intimidating” people and lobbying them to not sign the abortion petition, Coleman responded, “Absolutely I was there encouraging people to decline to sign.”

Meanwhile, Arizonans for Abortion Access sued the state over language drafted for the voter guide that used the phrase “unborn human beings,” arguing it violated laws requiring neutral language and was medically inaccurate. In August, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that the voter guide can use the term “unborn human beings.”

Defending the ballot initiatives in court drains campaigns of resources and time that could be utilized to mobilize voters. “Campaigns are now having to pay for lawyers and deal with litigation,” Toni Webb, deputy director of ballot initiatives for the ACLU, told Politico. “And it also creates uncertainty and confusion in voters’ minds when they see all of this.”

In many states, legislators have proposed laws that would change the requirements for ballot initiatives to make passage more difficult.

- This year, the Florida legislature considered — but ultimately did not adopt — a law that would have raised the percentage of votes required to amend the constitution from 60% to 67%.

- In Arizona, conservative lawmakers put a measure on the ballot in 2024 that, if passed, would make it much harder to gather enough signatures for citizen initiatives. Currently, to get a constitutional amendment measure on the ballot, organizers need to gather 15% of all votes cast in the latest governor’s race. Under the new proposal, organizers would need to gather the same 15% in each and every one of the state’s 30 legislative districts.

- In 2023, conservatives proposed a bill in Oklahoma that would have required certain ballot measures to receive both 50% of all votes and 50% of the votes cast in two-thirds of the state’s counties. The measure also would have limited ballot measures to odd years, when voter turnout is generally lower.

- Another bill proposed in North Dakota would raise the necessary number of signatures, require measures to pass in both a primary and general election to be enacted, and require initiatives to only address a single subject.

- This year, Arkansas enacted a measure that requires organizers to gather signatures in 50 counties. Previously, only 15 counties were needed.

- Months before Ohioans voted on their abortion-rights initiative in 2023, lawmakers proposed State Issue 1, which would have increased the number of signatures required to get an initiative on the ballot and raised the threshold for passage from a simple majority to 60%. In a special election in August 2023, Ohioans rejected this measure.

Missouri ballot measure faces mounting opposition

Records we obtained in Missouri show how one legislator has sought to subvert the democratic will of his constituents, who successfully added a measure related to abortion rights to the November 2024 ballot, by trying to amend the ballot initiative process.

Earlier this year, 380,000 Missourians — more than double the number required — signed a petition to put a constitutional amendment on the ballot that would allow abortion up to the point of fetal viability (typically 23 or 24 weeks into a pregnancy).

In response, conservatives in the state pushed a bill that would have made it much harder to pass any constitutional amendment via a ballot initiative. The legislature considered — but ultimately did not adopt — a bill that would have changed the citizen initiative process to include a constituent majority measure. This would require both a majority of voters to approve constitutional amendments and a majority of votes in the majority of Missouri’s eight congressional districts.

American Oversight obtained records from state Sen. Mike Moon — a staunchly anti-abortion rights legislator — and his staff that provide a behind-the-scenes look at Moon’s efforts to promote the ballot initiative bill as a counter-attack to the abortion-rights constitutional amendment.

In the records, Moon’s policy director directly tied Moon’s desire to defeat the measure to his support for adding a concurrent majority measure to the initiative petitions. Moon’s chief of staff suggested collaborating with Priests for Life, a Catholic anti-abortion rights group, to defeat the amendment.

American Oversight also obtained documents related to the “decline to sign” campaign launched by anti-abortion activists in Missouri, which discouraged people from signing the ballot measure petition and pushed those who had signed to withdraw their signature through the secretary of state’s office. The records include examples of signature withdrawal forms and emails from anti-abortion rights groups regarding the campaign.

We have filed more than two dozen public records requests in seven states that could shed more light on efforts to stifle ballot initiatives. We submitted public records requests to select elected officials and government agencies in Arizona, Florida, Michigan, Nebraska, Nevada, Ohio, Missouri, and Montana for communications about abortion rights ballot initiatives as well as communications with anti-abortion groups.