New Documents Show CDC Officials Dealing with Early Covid Testing Problems

American Oversight obtained more than 2,000 pages of documents from the early months of the pandemic that illustrate the CDC’s struggles to create and implement reliable Covid-19 testing.

On Jan. 21, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the first Covid-19 case in the United States. Later studies suggested that the novel coronavirus may have already been circulating in the U.S. for weeks.

While other countries quickly jumped into rigorous testing to track the virus’ spread, the U.S. fell behind, thanks in part to a flawed CDC test and bureaucratic hurdles that hindered the creation of other tests. Since then, research has found that the U.S. could have prevented hundreds of thousands of coronavirus-related deaths had it implemented sufficient mitigation measures in the spring of 2020, including aggressive and widespread testing.

American Oversight has obtained more than 2,000 pages of documents from the early months of the pandemic that illustrate the CDC’s struggles to create and implement reliable Covid-19 testing. The documents include communications among CDC officials and officials at the Food and Drug Administration, and make clear that problems with tests were present as early as the first weeks of February.

On Feb. 4, the FDA granted emergency use authorization (EUA) to the CDC’s Covid-19 test, which was the first coronavirus test authorized in the United States. The test was created by a team headed by Stephen Lindstrom, who had helped create earlier flu tests and was then the head of the CDC Respiratory Diagnostic Laboratory. It was made up of N1 and N2 components, which focused on identifying SARS-CoV-2, and an N3 component that was meant to identify a wider variety of coronaviruses. The documents obtained by American Oversight echo earlier reporting from the Washington Post that this last component had multiple problems.

In a Feb. 8 email, Lindstrom encouraged states to begin testing for possible Covid-19 cases. He wrote: “Please coordinate with the states […] to test at the state lab if they have verified performance of the test in their lab. These PUI [person under investigation] specimens no longer need to be shipped to CDC for initial testing if the state is able to perform testing.”

But that same day, Debra Wadford, from the California Department of Public Health, sent an email with the subject line “Issues with EUA Kit?” She wrote, “We are hearing from some local PHLs [public health laboratories] that they are picking up hits with the N3 target.” The next day, Wendi Kuhnert-Tallman, CDC senior adviser for laboratory science, said that she had “heard from a few that they are having trouble with the test” and expressed concern about whether the CDC was addressing these complaints.

As the Post reported, the CDC attempted to fix problems with the N3 component. On Feb. 11, Lindstrom circulated an email with a draft message for U.S. laboratories. He wrote, “FDA gave concurrence yesterday evening to allow CDC to distribute a new N3 assay component as a resolution.”

But according to the Post, by Feb. 14, more than three dozen laboratories had experienced problems with the CDC’s test. That week, the CDC acknowledged that the test kits it had sent to states were flawed.

On Feb. 16, FDA officials asked for more information about the tests. Lindstrom acknowledged that the CDC had received “reports regarding sporadic aberrant reactivity resulting in false positive results.” He wrote that the “reactivity is more often reported with the N3 assay component of the test.”

According to the documents, the CDC also had trouble processing testing samples. On Feb. 20, CDC official Darin Carroll asked Lindstrom to run some samples that had been split between multiple labs. Lindstrom replied in confusion, and later said, “We need to discuss and resolve a number of issues.”

On Feb. 22, Alana Sterkel, an assistant director at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, asked for assistance with the delivery of a “high priority sample” to the CDC in Atlanta. CDC officials attempted to “pull some strings” to get the sample delivered that same weekend, but later communications indicate that the sample still had not been received late in the day on Feb. 23.

On Feb. 23, Timothy Stenzel, the director of the FDA’s Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health, conducted an inspection and found that the laboratory conditions for making the test kits at the CDC headquarters in Atlanta were substandard. Federal officials later verified that lack of proper protocols at two CDC labs had contaminated these first tests. Two days later, according to the records, Stenzel sent an email with the subject line “Revisiting use of existing CDC kits at PHL labs for N1 + N2 only.” Lindstrom replied, “Please let us know what the current plan is.”

Also on Feb. 25, Jeff Shuren, the director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, asked, “Was CDC on board with the N1/N2 interim approach?” Stenzel replied that some individuals were on board, and that he was “working on the rest of the team.”

On Feb. 26, Ellen Flannery, director of the FDA’s office of policy, wrote that given the issues with the N3 component, the “FDA does not object” to state labs using a version of the CDC test that used only N1 and N2 components. That same day, the FDA told CDC officials that public health laboratories could use the test without the N3 component.

On Feb. 27, Stephanie Caccomo, the FDA’s media relations director, forwarded to colleagues a Politico article about then-HHS Secretary Alex Azar having told lawmakers that morning that 40 public health labs could now test for the coronavirus using just the N1 and N2 components. Shuren replied, “The bottom line is that the 40 or more labs can proceed to test now […]. And, as an aside, we told CDC they could do it. It’s their lab folks who had to warm up to the idea so any hold up was not on our end.”

But states continued to report problems even after the N3 component was removed. On March 2, Dan Jernigan, the director of the CDC’s Influenza Division, reported that Texas officials were frustrated with the unreliability of the CDC’s test. The FDA later concluded that contamination in CDC’s Atlanta labs may have compromised the N1 component as well.

Meanwhile, strict FDA regulations had hampered the testing ability of clinical laboratories that had developed their own tests but were struggling to get emergency FDA approval. The Washington Post reported that at this time, health officials were urging the FDA to ease the authorization process so that broader testing could be available. On Feb. 29, the FDA allowed clinical laboratories to begin using their own coronavirus tests before all the necessary paperwork had been filed.

Other Emails in the Documents

The documents also include early communications between Lindstrom and officials at the World Health Organization regarding a U.S. commitment to share testing technology abroad. On Feb. 2, 2020, Lindstrom emailed several colleagues, “PLEASE do not speak to WHO on our behalf regarding deployment strategies of reagent kits.” On Feb. 4, he emailed Mark Perkins, the chief scientific officer at the WHO, and said, “sorry for conflicting messaging from CDC. There are often several different people who get involved and the message can get confusing as it is passed along the chain.”

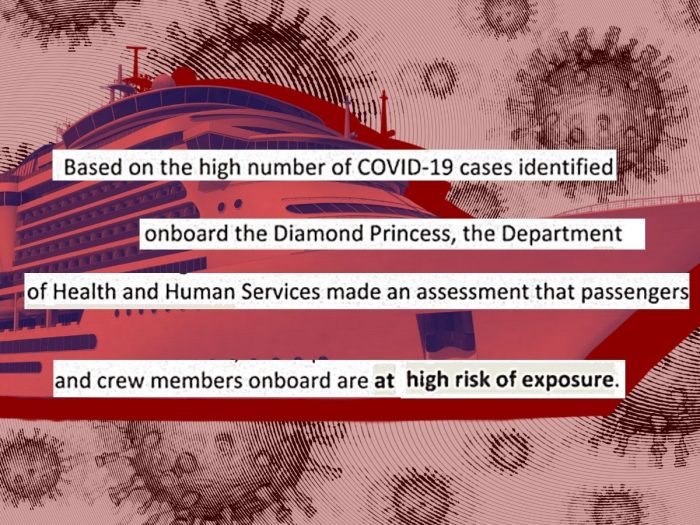

At the time, officials were also coordinating with the Japanese government about repatriating Americans who were on the Diamond Princess cruise ship. On Feb. 17, Americans from the ship began boarding flights to go back to the United States. Communications from that time show Japanese health officials asked for more information about the rationale for evacuating U.S. passengers, and told CDC and HHS officials, “We are confused with your messages to GOJ [Government of Japan] and to passengers on board.”

Finally, a March 14, 2020, email from a New Jersey-based infectious diseases doctor was forwarded to multiple CDC officials. The doctor wrote about Covid-19 cases he was treating: “This is clearly not what we are being told about risk groups…These were not immunocompromised people.”

These documents include more information about early agency coordination failures and warnings about PPE and test shortages, as well as federal officials’ communications with states and private companies. For more about early failures in the pandemic response, visit our Covid-19 Oversight Hub.