Records Shed Light on Troubling Conditions at Brooklyn Metropolitan Detention Center During 2019 Power Outage

Documents show inmate complaints about medical care, use of force information, and records indicating extreme temperature fluctuations in the days following the blackout.

American Oversight’s Freedom of Information Act efforts have uncovered complaints about access to medical care, documents about use of force, and records about other significant health and safety concerns surrounding the weeklong partial power outage that gripped the Metropolitan Detention Center (MDC) in Brooklyn, N.Y., two years ago.

MDC Brooklyn is a federal facility operated by the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) that typically houses more than a thousand people awaiting trial or serving sentences. The blackout was caused by an electrical fire on Jan. 27, 2019, and power wasn’t restored until Feb. 3, according to a Justice Department Inspector General report. The facility suspended social and legal visits during the outage, which coincided with a polar vortex that shot local temperatures down into the single digits, leading to protests and lawsuits over conditions.

American Oversight submitted a series of Freedom of Information Act requests shortly after the event and sued for records in July 2019. Among the records American Oversight has received in response so far are complaints about conditions and medical access, reports indicating the use of restraints or force on inmates before and during the outage, as well as logs showing extreme temperature variations in the days after the outage.

This report is part of American Oversight’s continuing investigation into inequity in the U.S. criminal justice system, including the often inhumane treatment of people held in custody. This issue has only become more urgent as the Covid-19 pandemic continues to ravage detention facilities, including MDC Brooklyn.

Delayed Medical Care and Lack of Access to Medication

The records we obtained include a series of complaints requesting compensation for damages related to events during the blackout, many of which appear to have been denied. The complaints contain firsthand accounts from inmates describing sometimes harrowing experiences involving delayed medical care — both in addressing emergencies and in managing chronic conditions such as sleep apnea, diabetes, or asthma — as well as other sanitation and health issues. The complaints, which typically requested sums of around $1 million, appear to have been largely unsuccessful. The records obtained by American Oversight so far include many denials, but no approvals, although the accounts are consistent with much of the contemporaneous reporting and related testimony.

In one complaint, an inmate alleged delayed treatment after they swallowed razor blades in a state of serious distress. “l suffered from: insomnia, asthma-related coughing and chest pain and tightness that were intensified by the cold, dizziness and headaches, and severe stress, fear, and mental health symptoms that caused me to swallow razor blades,” the person recounted.

“I was not provided with an inhaler for my asthma symptoms or with my prescription medication which I take daily to manage my mental health symptoms,” the complaint continued. “Because I had swallowed razor blades, I asked to be taken to the hospital multiple times, but multiple correctional officers and medical staff refused, saying there was nothing they could do.”

According to a memo written by Health System Administrator Gerard Travers that described medical emergencies during the blackout, a person who swallowed razors was taken to the hospital on Feb. 2. The memo, dated March 22, 2019, said the hospital transfer was delayed after protesters “detained” the ambulance, so the patient was instead taken in a government car. Travers also detailed several other cases in which people were moved to a hospital or local emergency room, including someone transported on Jan. 28 who was later diagnosed with multiple lung abscesses and pulmonary embolisms, as well as a dialysis patient experiencing chest pains taken to the hospital on Jan. 30, where they were diagnosed with a blood infection.

Many other compensation claims describe issues accessing care or medication, sometimes with devastating results. According to the inspector general (IG) report, inmates at MDC Brooklyn receive medication two ways: twice-a-day deliveries of pills and insulin from health staff, and permission to “self-carry” multiple days’ worth of medication at once, with refills requested through a computer system five days in advance of running out. The IG determined that staff “made all but one of the sampled insulin deliveries and all but two of the sampled pill deliveries” during the blackout. Although the computer refill system for “self-carry” medication was down during the outage, staff told the IG that inmates could request refills from staff during daily rounds or via a written request.

Many other compensation claims describe issues accessing care or medication, sometimes with devastating results. According to the inspector general (IG) report, inmates at MDC Brooklyn receive medication two ways: twice-a-day deliveries of pills and insulin from health staff, and permission to “self-carry” multiple days’ worth of medication at once, with refills requested through a computer system five days in advance of running out. The IG determined that staff “made all but one of the sampled insulin deliveries and all but two of the sampled pill deliveries” during the blackout. Although the computer refill system for “self-carry” medication was down during the outage, staff told the IG that inmates could request refills from staff during daily rounds or via a written request.

However, many of the inmate complaints allege they were unable to or unaware of how to make those requests. Multiple inmates claimed they did not receive their regular insulin shots. “During the blackout, I had no access to my insulin shots,” one wrote, adding that they “almost went into diabetic shock.” Another wrote that they typically received two insulin shots a day, but received shots only three of the seven days of the blackout, leaving them feeling “sick and nauseous.”

Others described serious health outcomes caused by lack of access to other medications or treatment, including HIV treatment. One person wrote that the disruption in medical care for managing an atrial fibrillation resulted in their having suffered heart palpitations, causing them to be “hospitalized for more than a month.” Another, who said they had previously been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, described delayed treatment for an apparent heart attack brought on by anxiety from being “locked in for two full days in the dark and cold.”

“I pushed the emergency button in my cell and nothing happened,” they said. “Eventually, the officers said they would take me to medical and I had to wait longer until the officers brought a stretcher to my cell, because they were short-staffed.” They were taken to the Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center for treatment for five days, where according to the complaint they were shackled to their hospital bed. “I now have to take heart medications because of this incident that I didn’t take before the blackout,” they wrote.

Another person wrote that they had recently transferred to MDC Brooklyn with a limited supply of a heart medication, which they said ran out on the second day of the blackout, and “no thermals or warm clothes the entire time.”

“There was no way to put requests for medicine in because the computers were not working,” they said in the complaint. “I told medical when they came around to distribute pills and they took my name down, but they never came back to see me or give me a refill of my medicine.” Their medication wasn’t refilled until days after the blackout ended, according to the complaint.

Some described a lack of access to mental health medications and services. One person wrote that they “suffer from depression, ADHD, bipolar disorder and suicidal thoughts,” but did not receive their medication during the blackout despite attempts to get the attention of corrections personnel. “I was on suicide watch. I attempted suicide until my cellmate took the noose out of my hands,” they added.

A number of complaints also address lack of access to electricity to run continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines, which are used to treat sleep apnea, a potentially life-threatening condition that causes difficulty breathing while asleep.

“I was scared to fall asleep because I did not know whether I would die in my sleep,” wrote one person with the condition. “Even though I made complaints and requests for medical attention since the first day of the blackout on January 27, 2019, I was not transferred to another part of MDC with electricity until February 2, 2019.”

The IG report confirmed that 15 people in the facility who used CPAP machines “were unable to do so for the first 6 days of the power outage because in-cell electrical outlets were nonoperational and because institution staff did not provide alternative accommodations.”

Incident Review Reports and Safety Concerns

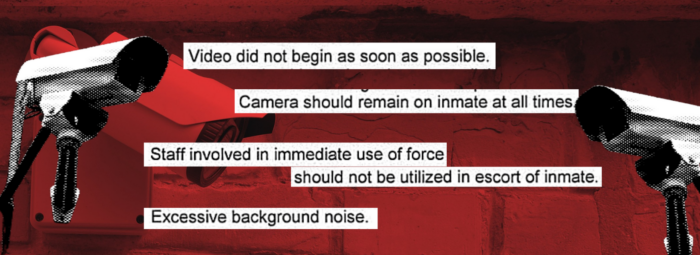

American Oversight also obtained a series of “After Action Review Reports” about apparent uses of force or restraints at MDC Brooklyn during and in the weeks before and after the blackout. The reports offer few details about the incidents, but give information about the date and time.

The records appear to show that the facility had determined that use of force was appropriate in almost all the cases, with the possible exception of a report about an incident on Jan. 19, before the power outage, in which the determination was redacted. However, each of the forms also noted “discrepancies” or criticisms for how the use of force or restraints was handled.

None of these records appear to have mentioned excessive force. Instead, many noted issues related to documentation, such as poor camera angles and unexplained breaks in recordings. Several of the reports relating to incidents that occurred during the blackout noted that the forms were “not completed in a timely manner due to civil disturbance and an electrical fire.” Others from before the outage listed other problems, including medical assessments that were “not thorough.”

The compensation claims also show apparent safety concerns regarding staff actions — or inaction.

“Pepper spray was used for a cell extraction in my unit, and the spray entered our cells where we were confined on lockdown with no way to escape the noxious air,” one inmate reported.

Others describe inadequate levels of supervision. In one complaint, an inmate said guards ignored them when they were attacked by seven or eight other prisoners, in apparent retaliation for breaking a hunger strike carried out by some during the blackout. The person required nine staples to the head and was taken to a hospital for treatment, according to the complaint.

“The officers on the unit turned a blind eye to my beating while it was happening and failed to intervene and protect me from the attack, which was very obvious because it involved so many people on the unit and took a long time,” the person wrote.

Extreme Temperatures

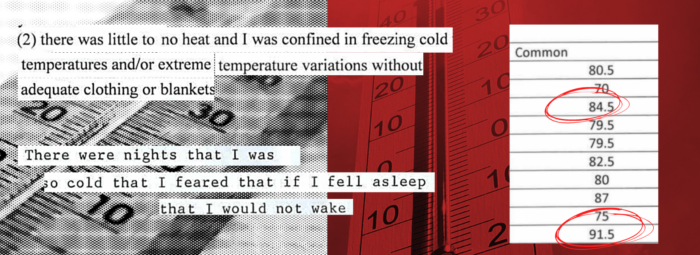

American Oversight also received records related to temperature issues at MDC Brooklyn, one of the most widely reported problems at the time. Multiple accounts in the compensation claims detail frigid conditions during the outage, which occurred during a major cold weather event.

“There were nights that I was so cold that I feared that if I fell asleep that I would not wake up,” one person wrote. Other complaints said staff did not provide or denied prisoners additional clothing and blankets to keep warm.

Temperature logs covering the days after the outage that were produced to American Oversight show temperatures, including some that reach extreme highs, that required adjustment by staff. For example, a log from 5:45 a.m. on Feb. 9 shows a range of 67 to 88.5 degrees across various units. It includes a note that two cells were “not at normal temperatures” and that temperatures “went up about 7 degrees for the building” after the staff member started a second hot water pump. Another log from Feb. 14 shows temperatures for two common areas reaching 91.5 and 90 degrees, with temperatures in the cells reaching the upper 70s, one even as high as 85.5.

The IG found “significant heating issues” at the facility during the power outage, but determined that they were unrelated to the electrical fire that caused the outage, as it did not affect the heating system. “Instead, long-standing temperature regulation issues caused temperatures in certain housing units in MDC Brooklyn’s West Building to drop below the BOP target of 68 degrees before, during, and after the power outage,” the report said.

However, the report also noted that it did not have full records of temperatures during the outage because “facilities staff did not record temperature measurements during the first 3 days of the power outage” and that the records for the remainder of the blackout were incomplete because staff “did not always record measurements for every housing unit or record the time they took the measurements.” The IG further noted that even when measurements were taken before and after the outage, they may not have been accurate because staff “did not use equipment appropriate to measure air temperature.”

One of the compensation complaints said staff selectively measured temperatures during the outage in a way that disguised the full conditions at the facility. Some inmates “blocked their ventilation ducts in an effort to prevent the exceptionally cold air from entering their cells,” according to the complaint. Staff on at least two occasions “entered the housing unit and presented to a particular cell where the air vent had been blocked, and recorded a temperature reading that was much warmer than the temperature in other cells.”

The IG report found that the measurements that were taken showed significant fluctuations: One area hit a low of 59 degrees the week before the blackout. During the event, “8 of the West Building’s 18 housing areas had at least 1 recorded temperature measurement below 68 degrees.” However, even with those lows, the report said that the average in the facility was 70 degrees — above the facility’s target temperature — due to high temperatures in other areas caused by long-standing HVAC problems.

The irregular temperature measurements taken by staff and the significant variations across the facility make it hard to gauge the full extent of the issues before, during, and after the outage. But the fact that one of the most prominently reported issues during the outage appears to have been tied to pre-existing facility maintenance problems highlights the substandard conditions regularly faced by people in criminal detention.

American Oversight will continue to investigate inhumane treatment within our criminal justice system, including the government’s response to incidents like the 2019 MDC Brooklyn power outage as well as efforts to contain the spread of Covid-19 among inmate populations.