The Far-Right Attack on Education: How Curriculum and Classroom Censorship Stifles Educators, Harms Students, and Threatens Our Democracy

In a far-reaching attempt to reshape and ultimately weaken public education, far-right politicians and activists have pushed to restrict classroom discussions of racism and gender, curtail the rights of LGBTQ+ students and teachers, and ban books unilaterally deemed "inappropriate." Since 2021, 23 states have adopted educational gag orders limiting speech that doesn’t fall within narrowly proscribed political views.

Download the Report

Executive Summary

In a far-reaching attempt to reshape and ultimately weaken public education, far-right politicians and activists have pushed to restrict classroom discussions of racism and gender, curtail the rights of LGBTQ+ students and teachers, and ban books unilaterally deemed “inappropriate.” Since 2021, 23 states have adopted educational gag orders limiting speech that doesn’t fall within narrowly proscribed political views.1

American Oversight has obtained and analyzed thousands of pages of public records to shed light on these efforts to politicize, censor, and dismantle public education, from early elementary through higher education. This report details documents obtained from dozens of records requests that provide a behind-the-scenes look at how the implementation of “divisive concepts” measures threatens the foundational principles of public education and democracy, creates confusion for educators, and undermines the provision of a comprehensive education. This report covers the following:

- Distortion of Educational Content: Public records reveal ideologically motivated censorship of educational materials that privileges politics over truth. This includes removing references to race, gender, and sexual orientation; excising certain words or lessons; altering and whitewashing discussions of history; or banning certain books.

- Harm to Educators and Students: Targeting certain content through vaguely defined terms like “divisive concepts” has a chilling effect on educators, who are left confused, uncertain, and fearful of adverse employment consequences — and more inclined to excise content related to race, gender, or sexuality. Consequently, students are denied the opportunity to learn about the full range of human experiences and ideas.

- Undermining Public Education and Democracy: Politically motivated censorship of educational content has been embraced by those seeking to weaken public education, and threatens to leave students with an inaccurate, incomplete, or biased understanding of U.S. history and current social issues, thus undermining the foundation of a healthy democracy: an informed electorate.

With Donald Trump back in the White House, the restrictive state-level policies outlined in this report are already moving to the federal government. The 2024 Republican Party platform called for cutting federal funding for schools alleged to be teaching critical race theory and “radical gender ideology.”2 Similarly, as part of its agenda to overhaul the U.S. education system, Project 2025 — a set of policy proposals put together in advance of the 2024 presidential election by the Heritage Foundation and Trump allies, several of whom have since been appointed to key administration positions — calls for federal lawmakers to draft legislation banning the teaching of supposed gender ideology and critical race theory and for officials to adopt “divisive concepts” policies for K-12 systems.3 Less than ten days into his second administration, Trump began implementing this agenda. He signed executive orders directing federal agencies to end K-12 “indoctrination” and to enact a federal school choice program.4 Underpinned by public reporting and government records from several states that unveil new details about the implementation of and responses to such policies, American Oversight’s report offers a unique look at the harmful effects of politically motivated censorship measures on students, educators, and our democracy.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Rewriting the Response to Racial Justice Protests

The Trump Administration’s Response

In the States

Christopher Rufo’s Revolution of Lies

What (and Where) Is Critical Race Theory?

III. How These Laws Affect Educators and Students

Confusion and Unanswered Questions

The Chilling Effect

Denying Students a Full Education

IV. The End Game: A Far-Right Alternative to Public Schools

V. Conclusion

Records Obtained by American Oversight

Endnotes

I. Introduction

Democratic ideals and multicultural society have been under attack on multiple fronts, including in public education. Across the country, students face restrictions on how they can express themselves both within and outside of the classroom. Teachers fear punishment if they dare to openly and honestly discuss America’s fraught relationship with race. Books are being banned for mere mentions of gender or sexuality. And educational materials face revision, excision, and censorship to reflect a far-right worldview.

The current censorship movement took off toward the end of the first Trump administration, taking advantage of the backlash to inroads made by racial justice movements nationwide.5 In the wake of protests spurred by the 2020 police killing of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, some schools responded by adding curriculum materials that examined racism in America’s past and present, condemning racism and making public statements in support of Black students and their families, or taking other steps to examine and address structural inequities in education.6

Some parents and politicians recoiled at what they labeled “left-wing indoctrination,” demanding that school districts remove any materials or instruction that smacked of what they believed to be “critical race theory.”7The Trump administration quickly translated those anxieties into policy. In September 2020, President Trump banned diversity trainings in the federal government and for federal contractors.8 The White House also established the President’s Advisory 1776 Commission, which called for the rejection of “any curriculum that promotes one-sided partisan opinions, activist propaganda, or factional ideologies that demean America’s heritage, dishonor our heroes, or deny our principles.”9

In states across the country, politicians have implemented this censorship campaign with great fervor. Prohibitions targeting instructional materials that explore identities or ideas outside of white, Christian, or heteronormative perspectives have coincided with bans on both classroom discussions of “divisive concepts” — a vague term used to cover a range of ideas — and instruction about sexual orientation and gender identity in specific grades.10

This political crusade has bewildered educators nationwide and left them in fear of politically motivated termination. Public records obtained by American Oversight and detailed throughout this report reveal how the array of censorship measures have created ambiguous legal lines, the effect of which is a pronounced chilling effect: Vague laws beget unclear guidance at the district level, leaving educators to err on the side of being overly cautious as they decide which instructional materials may be out of compliance.

For example, faced with little to no guidance from state educational leaders, educators in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina removed a book from a second-grade lesson plan for referring to a character as “they.”11, i The Florida Department of Education left math textbook publishers so unsure about how to comply with state law that some removed math stories that contained references to other cultures — for example, substituting a story about the global history of tea with another about an animal hospital.12, ii In Arkansas, officials claimed a story might violate the state’s divisive concepts executive order because it included a character who was a Vietnamese monk.iii Public records also reveal how politically driven but ill-defined measures such as Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s 2022 divisive concepts executive order result in the purging of terms like “racist” or “white supremacist” in history lessons.13, iv Whether these measures were motivated by confusion and fear or political calculations, students are left less informed about the world around them, the challenges faced by marginalized communities, and how our government has sometimes failed to live up to the standards established in our founding documents.

Now, as Trump begins his second term, more emboldened than ever to carry out his anti-democratic agenda, he is poised to use the power of the federal government to renew a push for national policies that will narrow what students can learn, remove protections for LGBTQ+ students, and further erode public education. His nominee for education secretary, Linda McMahon, is the board chair for the Trump-aligned America First Policy Institute, a think tank critical of both pro-LGBTQ+ policies and those that promote “radical ideologies over core subjects,” and supportive of reinstating Trump’s 1776 Commission.14 Trump has also filled key administration positions with authors of the Heritage Foundation’s 2023 “Mandate for Leadership: the Conservative Promise,” commonly known as Project 2025. The project, which serves as a playbook for a hostile far-right takeover of the federal government, outlines major changes to federal education policy, censorship of learning materials, discrimination against LGBTQ+ students, and radical cuts to — or even eradication of — the U.S. Department of Education.

II. Rewriting the Response to Racial Justice Protests

As noted in a 2021 report from PEN America, the “public reckoning” with racism that sparked widespread protests in the summer of 2020 “led many American institutions in various fields to adopt new curricula, training, and commitments to confront and dismantle racism.”15 The effort did not go unnoticed by politicians and activists,16 including then-President Trump, who blamed the protests on “left-wing indoctrination” in schools and called for districts to remove anti-racist educational materials.17 The first Trump administration announced a ban on federal racial sensitivity trainings and created a commission tasked with promoting “patriotic education” in schools.18, 19, 20 Conservative state leaders took up the mantle by banning education materials purportedly containing “divisive concepts” and passing “Parents’ Bill of Rights” legislation targeting instruction on gender identity and sexual orientation.

The Trump Administration’s Response

The May 2020 murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by a police officer in Minneapolis sparked a national conversation about systemic racism.21 Many school districts released public statements committing to center racial justice principles in their work,22 created racial equity policies,23 or questioned whether current curricula accurately taught such issues.24 In August 2020, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam announced a new African American history elective course for high school students, developed by the Virginia Department of Education, Virtual Virginia, WHRO Public Media, history instructors, and historians.25 In 2021, the College Board retained a committee of history instructors to begin developing a national Advanced Placement (AP) African American Studies course.26 A 2021 study conducted by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University found that after Floyd’s murder, teachers used crowdfunding platforms to request more anti-racism instructional materials than they had after any similar event in the previous decade.27 Several schools considered implementing curricular resources developed to teach “The 1619 Project,” a series of essays published the previous year by the New York Times to commemorate the 400th anniversary of enslaved Africans arriving in Virginia.28 The 1619 Project aimed to “reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.”29

Far-right activists and politicians immediately disparaged the 1619 Project as a left-wing threat to unravel the nation.30 In July 2020, Sen. Tom Cotton introduced a bill that would have banned federal funding for teaching the 1619 Project in K-12 schools,31 describing the project as “a racially divisive, revisionist account of history”32 and calling slavery a “necessary evil upon which the union was built.”33 The month prior, Cotton had suggested calling the protests the “1619 riots” after someone spray-painted 1619 on a toppled statue of George Washington.34 That September, Trump said on social media that his administration would investigate whether California schools were using 1619 Project curriculum materials, pledging to defund them if so.35Trump also appeared to see the protests as an opportunity to promote charter schools and voucher programs, claiming during a June 2020 press conference about police reform that “school choice” was the “civil rights statement of the year.”36

President Trump enshrined far-right resentment against the anti-racism movement that September in Executive Order 13950. The order prohibited the use of trainings in federal workplaces that espoused “divisive concepts,” which the order defined as including ideas that “an individual, by virtue of his race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive” or that “an individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment solely or partly because of his or her race or sex.”37 The order also required agency heads to ensure compliance with that prohibition, including through “performance-based adverse action” against supervisors or employees “with responsibility for promoting diversity and inclusion.”38 Use of the term “divisive concepts” in policymaking quickly took off, along with accompanying hazy and confusing definitions that could be used to prohibit a wide range of ideas.39 In the years since, at least 23 states have passed legislation limiting how instructors can discuss race, according to analysis by the Washington Post.40

Two months after issuing the order, the Trump administration established the President’s Advisory 1776 Commission, which called for “restor[ing] patriotic education that teaches the truth about America.”41 In his remarks establishing the commission, Trump blamed the 2020 protests on “decades of left-wing indoctrination in our schools” and warned: “Critical race theory, the 1619 Project, and the crusade against American history is toxic propaganda, ideological poison that, if not removed, will dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together. It will destroy our country.”42 The commission also served as a tool for promoting charter schools, with then-Education Secretary Betsy DeVos emphasizing the Trump administration’s support for school choice and arguing that instruction that “misconstrues” or “outright lies” about American history demonstrates why families need “more education options.”43

In January 2021, the commission produced “The 1776 Report,” which the American Historical Society criticized as consisting of a “simplistic interpretation” of America’s founding that “relies on falsehoods, inaccuracies, omissions, and misleading statements” while erasing enslaved people, women, and Indigenous communities.44 The report instructed schools to teach a version of American history that was “accurate,” “ennobling,” and “inspiring,” and called for states and school districts to “reject any curriculum that promotes one-sided partisan opinions, activist propaganda, or factional ideologies that demean America’s heritage, dishonor our heroes, or deny our principles.”45

Later that year, Hillsdale College, a small but influential Christian college, released its history and civics “1776 Curriculum” for K-12 schools, which reflected a similar minimization of the legacy of racism in U.S. history.46On the surface, Hillsdale is comparable to other small, midwestern liberal arts colleges. It enrolls fewer than 2,000 students on its Michigan campus in a town of about 8,000 that shares its name. But it boasts a more than $900 million endowment and has become a leader in the far-right movement’s reimagining of public education.47 The school has become a resource for activists who want to overhaul public education and use “divisive concepts” measures to eliminate diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. Through Hillsdale College’s Barney Charter School Initiative, the college aims to spread “extreme conservative thought” across the country by planting a network of so-called classical K-12 charter schools, which are characterized by their rejection of modern educational practices and culturally relevant curriculum in favor of Eurocentric texts and “Western canon.”48 The “classical” charter movement has deep connections to the conservative think tanks and activists at the vanguard of the censorship movement.49

Christopher Rufo’s Revolution of Lies

Far-right activist Christopher Rufo has played a leading role in fear-mongering about critical race theory in schools, helping inspire the wave of legislation that has perplexed and threatened teachers across the country.

Rufo, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute as well as at Hillsdale College, argues that CRT and diversity, equity, and inclusion programs encourage discrimination against white and Asian men.80, 81In September 2020, in an interview on Tucker Carlson Tonight that has been widely cited as the origin of President Trump’s interest in CRT, Rufo alleged that CRT “pervaded every institution in the federal government,” including in diversity trainings.82 Days after the segment aired, Russell Vought, then the head of the Office of Management and Budget, issued a memo instructing agencies to identify contracts or spending related to “any training on ‘critical race theory.’”83 Later that month, Trump issued Executive Order 13950, formalizing the memo’s ban on racial sensitivity trainings for federal employees and contractors.84 Trump later sent Rufo, who said he had provided research to the White House for the executive order, a pen from the signing with the note “Who says one person can’t make a difference?!”85

Rufo admits he has deliberately sought to broaden the definition of CRT, applying the term to anything he views as “unpopular”: “The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’ We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.”86 Confusion among educators about what CRT entails is hardly surprising when the panic is based on intentional misrepresentation.

If the terms he uses are deliberately ambiguous, his goal is not. Rufo has argued for a “counterrevolution” against antiracist principles and policies, modeled on Richard Nixon’s 1968 campaign and presidency.87 He has written that activists, intellectuals, and corporations are plotting to create an “anti-normative society” in which LGBTQ+ identities are “valorized.”88 The consequence of this effort to “re-engineer society,” he has said, is a “huge explosion” of young people adopting gender and sexual identities that are “not representative” of society at large.89 Such claims mirror the homophobic and anti-trans conspiracy theories that have inspired anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in conservative states.90 As Florida Gov. DeSantis warned attendees at the signing of the state’s “parental rights” bill, which Rufo attended:91 “They support sexualizing kids in kindergarten. … They support enabling schools to, quote, ‘transition,’ students to a, quote, ‘different gender,’ without the knowledge of the parent, much less without the parent’s consent.”92

In October 2023, Rufo announced a new fellowship to help other activists develop “a specific ‘culture war’ project.”93 The program promised a $1,000 honorarium for fellows, personal mentorship from Rufo, and connections with policymakers and the media.94 Earlier that year, Rufo had also hosted a private summit for activists to develop an “anti-woke policy agenda” for a future conservative presidential administration, calling for the U.S. Department of Education “to put a price on critical race theory-style discrimination in admissions, hiring, and programming” and the U.S. Department of Justice to use “civil rights law to create an anti-woke enforcement regime.”95

Far-right activist Christopher Rufo has played a leading role in fear-mongering about critical race theory in schools, helping inspire the wave of legislation that has perplexed and threatened teachers across the country.

What (and Where) Is Critical Race Theory?

Critical race theory, a term coined by civil rights scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, is an academic and legal framework pioneered by legal scholar Derrick Bell.96 The theory originated in the 1970s and 1980s, as academics and activists sought to explain why even after the civil rights movement, Americans continued to live in a perversely unequal society.97 Scholars analyze governments, schools, the health-care system, police departments, and other institutions to show how policies and practices — even those that are facially race-neutral — can still perpetuate racial inequalities.98 According to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, CRT proponents contend that racism “is more than the result of individual bias and prejudice” and instead is “a systemic phenomenon woven into the laws and institutions of this nation.”99

The anti-CRT censorship campaign has confused some educators. The theory is not commonly taught in K-12 schools or even undergraduate courses, despite claims to the contrary.100 In an example of how the supposed threat has been exaggerated for political purposes, one local school board member in Texas’ Granbury Independent School District, Courtney Gore, has since walked back the platform she ran on in 2021, when she promised to purge allegedly inappropriate lessons related to race and sexuality she had heard about on far-right media.101 After her election, she said she searched for the harmful content and found nothing. Gore has also warned that wealthy charter proponents are using panic about curriculum to destabilize trust in the public school system.102

In the States

Censorship bills quickly swept through conservative state legislatures.50 Most apply only to K-12 grade levels, but multiple states have also censored higher education.51 Critical race theory (CRT) has also been widely banned, with policymakers incorrectly affixing the “CRT” label to a range of curricula and instructional materials that reference race.52 A study conducted by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that in 2021 and 2022, federal, state, and local policymakers introduced 563 laws, policies, executive orders, and other measures aimed at restricting teaching about race and racism.53 Nearly half of these measures adopted language from Trump’s “divisive concepts” executive order.54

Race and racism aren’t the only concepts that have been targeted. Some states have passed “parental rights” legislation restricting discussion of sexual orientation or gender identity.55 Officials have used these vague laws to remove books that contain brief scenes of nudity or sexual themes. Some of these laws also contain provisions placing new restrictions on student and staff self-expression. Bills passed in Iowa, North Carolina, Indiana, and other states require schools to notify parents if their child requests to use another name or pronoun.56

In January 2022, newly elected Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin issued Executive Order 1, which aimed to “end the use of inherently divisive concepts, including Critical Race Theory” in K-12 public schools.57 Youngkin also instituted a tip line — quietly shut down the next year after receiving “little or no volume of responses” — for parents to share alleged violations of the executive order.58 Documents obtained by American Oversight revealed that the Virginia Department of Education received related help from right-wing circles, spending $10,000 to hire a consulting firm run by former Trump administration official Kimberly Richey to “provide subject matter expertise, review and evaluation, and policy advice related to inherently divisive topics and other provisions.”59, v At the time of her hiring, Richey’s resume outlined her work helping “[d]raft model legislation” to “[e]liminate critical race theory” in public schools.vi

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed multiple bills restricting classroom discussion of racism, gender, and sexuality, beginning in March 2022 with HB 1467.60 The law mandates that educational media specialists review books for prohibited content and requires school districts to publish instructional materials online and to create a system for objections to materials deemed not “grade level and age group” appropriate.61 That same month, DeSantis signed HB 1557, which prohibits instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity in certain grade levels.62 This was followed in April 2022 by DeSantis signing HB 7, which forbids classrooms from being used to “indoctrinate” students.63 In 2023, the Florida State Board of Education voted to extend prohibitions on instruction on gender identity and sexual orientation to K-12 schools.64

As references to race and gender were being excised, state leaders sought to expand charter and school choice initiatives and to infuse religion and far-right viewpoints into curriculum. In 2019, the Florida legislature passed HB 807, which required the Florida Commissioner of Education to review the state-adopted civics course materials in consultation with several named education stakeholder groups, including Hillsdale College.65 The commissioner also sought Hillsdale’s review of the state’s English and math standards in 2020.66 Documents obtained by American Oversight show that DeSantis’ allies were laying the groundwork for a new civics curriculum similar to Hillsdale’s.vii The state’s Civics Seal of Excellence program for teachers has also been criticized for espousing Christian nationalism and downplaying the role of race in contemporary political and social life.67 In 2024, DeSantis signed legislation streamlining the public-to-charter approval process.68 Under DeSantis, Hillsdale has thrived in Florida, where its six member schools stand out as its largest state network.69

In Tennessee, Gov. Bill Lee, advised by Larry Arnn, Hillsdale College president and head of Trump’s 1776 Commission, put Hillsdale College at the core of his anti-CRT crusade.70 In June 2021, Lee signed into law Tennessee’s divisive concepts legislation, which prohibited the inclusion or promotion of the same loosely defined concepts referred to in Trump’s executive order and other state legislation.71 As DeSantis did in Florida, Lee also encouraged the expansion of “classical” charter schools like Hillsdale, which at the time of this report’s publication has one member campus in Tennessee.72 Lee has publicly voiced a goal of increasing to 50 the state’s number of charter schools using Hillsdale curriculum.73 Education scholars have noted the alarming politicization of charter expansion: As Bruce Fuller, a professor of education and public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, told the New York Times: “I’ve never seen a governor attempting to use charters in such an overtly political way. … You’ve had governors who’ve encouraged the growth of charters to provide more high-quality options for parents, but it’s highly unusual to see a governor deploy the charter mechanism for admittedly political purposes.”74

On her first day in office in January 2023, Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders ordered the state Department of Education to find and remove curriculum materials alleged to promote CRT or “indoctrination.”75Months later, Sanders signed the LEARNS Act, which codified the order into state law and created a new voucher program to allow the use of public funds for private, parochial, or home schools.76

In North Carolina in August 2023, the General Assembly overrode Gov. Roy Cooper’s veto and passed SB 49, which prohibits “instruction on gender identity, sexual activity, or sexuality” for K-4 grades.77 The law, commonly referred to as the “Parents’ Bill of Rights,” also requires educators to notify parents if their child chooses to go by a different name or pronoun at school.78 Notably, the prohibited “instruction” is not defined in SB 49’s language, leaving much up to the interpretation of school districts and educators.79 That unclear language has created confusion and extra work for educators and administrators as they seek to comply with the legislation’s vague requirements.

III. How These Laws Affect Educators and Students

Across the country, states have passed laws restricting what students can be taught and what books they can access. While these measures may specify stiff penalties for teachers who violate the law, they are often vague about what content or ideas are prohibited. Guidance issued by school districts on how to interpret these laws can be similarly ambiguous — if it exists at all.

This lack of clear guidance creates confusion for school administrators and teachers as they navigate legal gray areas. As school districts struggle to interpret new restrictions, teachers err on the side of caution to avoid potential consequences, leading to a profound chilling effect on what is taught, shared, or discussed in classrooms, especially with regard to books or lessons related to African American and LGBTQ+ experiences.

Confusion and Unanswered Questions

The vague language used to describe “divisive concepts” in President Trump’s 2020 executive order banning diversity trainings for federal employees” was also used in state efforts to restrict classroom speech, producing more confusion than clarity. For instance, during discussions of racial disparities or the history of slavery, what specifically should teachers avoid saying to guard against the idea that “any individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race or sex”? What constitutes “promoting” or teaching an idea, as opposed to merely sharing it? “While these banned concepts may appear straightforward at first glance, their ambiguity comes to light when put into practice,” wrote U.S. District Judge Paul J. Barbadoro in his May 2024 decision striking down New Hampshire’s “divisive concepts” law.103

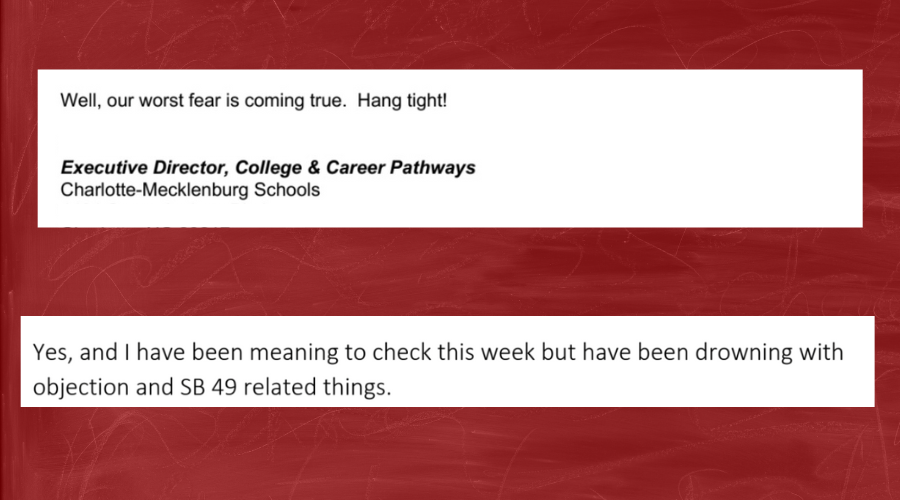

With the laws and executive orders failing to provide clear and applicable examples of banned topics, it’s been up to school administrators, and ultimately teachers themselves, to contend with the vagueness. Public criticisms as well as records obtained by American Oversight evince the frustration and confusion felt by administrators when faced with implementing new restrictions. Officials in North Carolina’s Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, for example, anticipated early on the challenges in helping teachers comply with SB 49, the state’s “Parents’ Bill of Rights” that went into effect starting in August 2023. “Well, our worst fear is coming true,” wrote one official in an email to colleagues the day the state legislature overrode Gov. Roy Cooper’s veto of the bill.viii The next month, another official, while responding to an email about an objection to a book, said they were “drowning with objection and SB 49 related things.”ix When a high school principal asked if a teacher’s bulletin board about banned books violated Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools policy, a school superintendent said he was sorry “that you have not received guidance on this.”x

About a week after SB 49 took effect, the North Carolina Association of School Administrators and the North Carolina School Superintendents’ Association held a webinar about the new law.xi The accompanying slideshow, obtained by American Oversight, mentioned “Concerns w/ vagueness and potential impact.”xii The slideshow also highlighted the lack of clarity around potential penalties for violating the law. “Employee penalties – vague,” one slide said. “[D]istricts must clearly communicate potential disciplinary action to all employees.”xiii Similarly, presentation slides from an October 2023 meeting of the Rockingham County Schools Parent Advisory Council reveal worries about SB 49’s redundancy, burdens, and vagueness. “[T]here are many parts of the bill that aren’t needed, and it creates extra work for school staff that may not have any real benefit or provide parents with more or different information.”xiv

Education advocates have highlighted the heavy administrative burden created by SB 49’s vague language. According to Sam LaFrance, the manager of editorial projects for PEN America’s Free Expression and Education team:

The administrative burdens of bills like SB 49 weigh heavily on many teachers, adding hours of work for those who are already stretched to the breaking point. Further, unclear enforcement mechanisms and vague definitions spur self-censorship, transforming schools into more combative and stressful places to work. Where educational institutions become a battleground in the culture wars, teachers’ jobs become harder, and students’ learning suffers — the fruits of educational intimidation at work.104

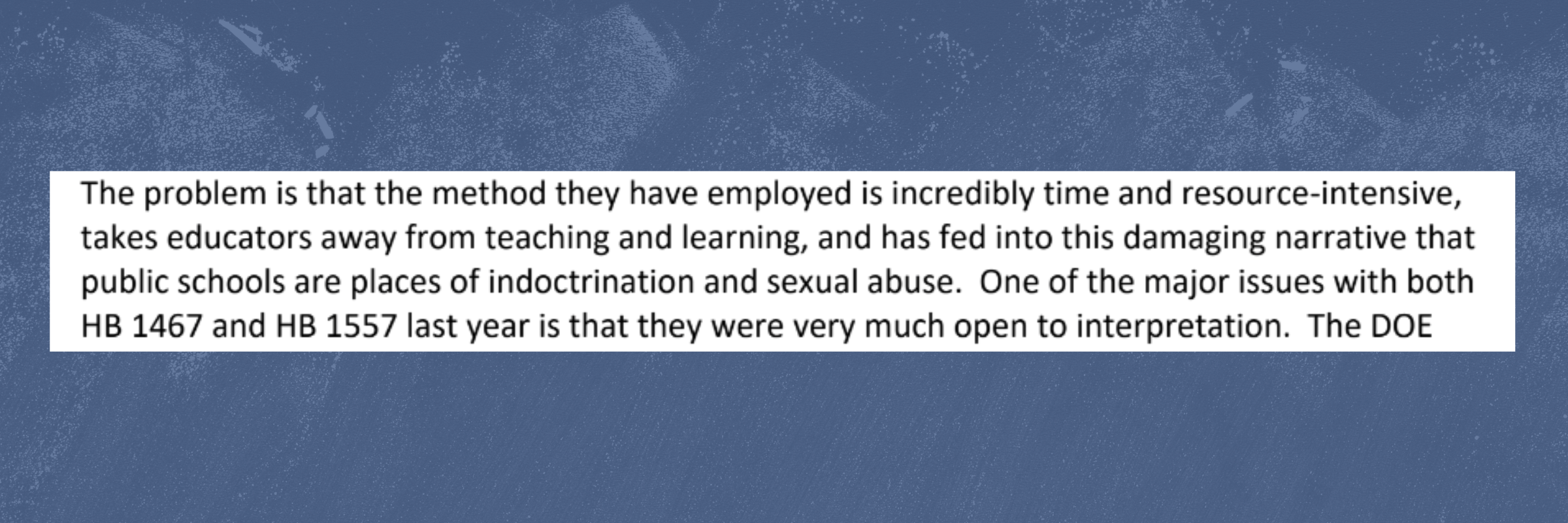

Public records obtained from the Brevard County School District reveal similar concerns about Florida’s spate of censorship bills, including HB 1069, which outlines the process for removing books from schools and limits classroom education on sexual orientation and gender identity. The Florida Association of District School Superintendents’ 2023 Legislative Summary detailed problems with HB 1069 that ranged from resource scarcity to anticipated difficulty for teachers in determining what was allowed. Implementation of the law was “incredibly time and resource-intensive” and took “educators away from teaching and learning,” while the requirement that committees “convene, read, review, and assess each of the challenged books” tied up district resources.xv And because the law did “little to put guardrails in place” on what could be considered objectionable material, “the mere reference to an LGBTQ person, or some sexual activity without any description of it, is challenged for including inappropriate sexual content.”xvi The summary continued: “This vagueness in the law forces each district to address these issues on their own, opening each up to challenge and criticism no matter what they do,” with the state’s Department of Education accusing districts of “manufacturing controversy” for following the department’s instructions to “err on the side of caution.”xvii

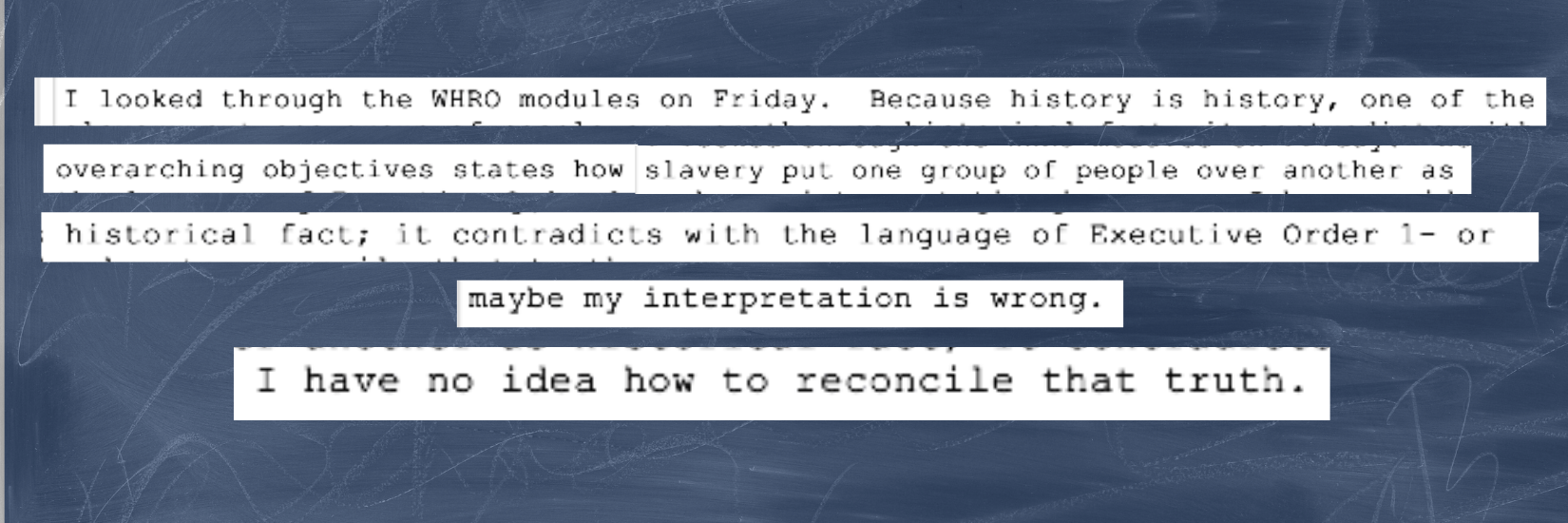

Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s 2022 “divisive concepts” executive order also proved difficult to interpret. In emails obtained by American Oversight, a Virginia Department of Education official expressed confusion and concern about the order. In one email from March 2022, the official emailed the chief diversity, opportunity and inclusion officer, pointing out that the modules of the state’s African American history high school elective course might conflict with the language of the order.xviii, 105 “Because history is history, one of the overarching objectives states how slavery put one group of people over another as historical fact,” the official wrote. “It contradicts with the language of Executive Order 1 – or maybe my interpretation is wrong. I have no idea how to reconcile that truth.”xix

As administrators struggled to create policies and guidance that correctly interpreted new restrictions, educators encountered on-the-ground difficulty in applying the vague language to their classroom practices. During January 2023 hearings in the New Hampshire House of Representatives about the state’s “divisive concepts” law, teacher David Scannell testified that he was uncertain about what essay topics he could approve. The statute seemed to bar teachers from advocating for measures like affirmative action, he testified, so if he approved a student’s proposal to write a paper in support of affirmative action, could he be violating the law? “Under the ‘divisive concepts’ law, is a teacher grading such a paper required to fail the student if he determines there [isn’t] any merit to American exceptionalism?” Scannell asked.106

In a February 2022 Washington Post article, Jen Given, a New Hampshire high school history teacher, said she was unsure how to interpret terms in the law like “inherently,” “superior,” or “inferior,” which were used in regard to the provision barring teaching that suggested one group was better than another.107 Given said that she had asked school lawyers, the teacher’s union, and the state for clarification but had not received helpful guidance. “It led us to be exceptionally cautious because we don’t want to risk our livelihoods when we’re not sure what the rules are,” Given said.108 In Judge Barbadoro’s decision striking down the law, which he condemned as “fatally vague,” he wrote:

The banned concepts speak only obliquely about the speech that they target and, in doing so, fail to provide teachers with much-needed clarity as to how the Amendments apply to the very topics that they were meant to address. … This lack of clarity sows confusion and leaves significant gaps that can only be filled in by those charged with enforcing the Amendments, thereby inviting arbitrary enforcement.109

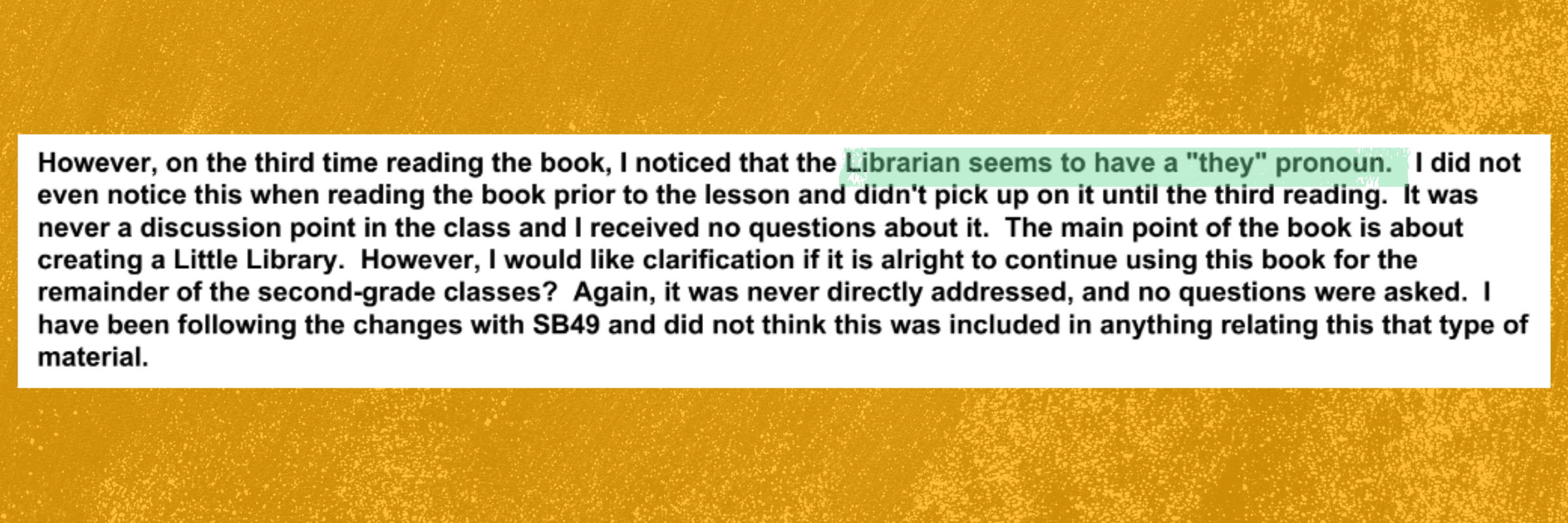

In North Carolina, records obtained by American Oversight reveal that an elementary school teacher’s assistant in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools who was editing a Hispanic Heritage Month presentation reached out to district officials after learning that artist Frida Kahlo was “in some way connected with LGBTQ community,” seeking in apparent good faith to comply with SB 49.xx They also asked the district for guidance on whether they could continue to read to second graders a picture book about a free neighborhood library after realizing the book — The Little Library — used the gender-neutral pronoun “they” for a character.xxi

Educators aren’t the only ones seeking — and not receiving — clarity on how to apply restrictions. In 2022, the Florida Department of Education released to American Oversight examples of math textbooks that it rejected for purportedly containing content related to CRT or social-emotional learning.110 The following year, thedepartment reportedly rejected 82 out of 101 social studies textbooks for containing objectionable materials, leaving publishers to alter text if they wanted their books to be accepted by the state.111

Records obtained by American Oversight shed light on the frustration textbook publishers experienced in seeking clarification from the department about requirements for math textbooks.112, xxii In April 2022, representatives from the curriculum developer Accelerate Learning sent several emails to the Florida Department of Education seeking clarification about why its math textbook materials had been rejected.113, xxiii In one email, an Accelerate representative asked for “more information” about why a fourth grade course wasn’t recommended.xxiv A few days later, another Accelerate representative asked, “Is there a way for us to get examples of what it looks like one reviewer found?” They added, “We worked really hard … to follow the guidance we were given from the DOE every step of the way so it surprises me that someone found that we specifically mentioned culturally relevant teaching.”xxv The representative followed up again after not receiving a reply, writing, “I know you all are swamped, but I also know these are time-sensitive things.”xxvi

The Chilling Effect

Public records reveal that in the absence of clear guidance about why their books had been rejected by the Florida Department of Education, Accelerate Learning ultimately replaced several lessons in the math books to remove references to different cultures.114 For example, a passagexxvii about Tropical Storm Pakhar — a 2017 storm that impacted southern China, southeast Asia, and the Philippines — was part of a lesson about the place value of whole numbers. It was replaced with a passage about invasive species in the Chesapeake Bay.xxviii Another story that explained the global history of coffee and tea, used to introduce adding and subtracting decimal numbers, was replaced with a passage about working in an animal hospital.xxix

As textbook publishers have erred “on the side of caution” by deciding to remove content that could be considered remotely controversial, school administrators and teachers have also removed curriculum materials and avoided classroom discussions out of fear of being penalized for violating the law. In its August 2022 report “America’s Censored Classrooms,” PEN America noted that laws prohibiting the promotion of certain ideas make it very easy for activists or school administrators to allege violations because “it is impossible to draw a clear line between teaching about a point of view and ‘promoting’ that point of view.”115 While one student could think the teacher is merely communicating facts, another student could consider the lesson a “ringing endorsement.”116 “Faced with such ambiguity,” the report noted, “the prudent teacher will be apt to self-censor,” leading to “a pronounced chilling effect on teachers.”117

A 2022 survey by the RAND Corporation found that approximately one-quarter of teachers said that “limitations placed on how teachers can address topics related to race or gender have influenced their choice of curriculum materials or instructional practices.”118 In January 2023, the National Association for Music Education (NAfME) found that about two-thirds of surveyed educators in states with “divisive concepts” laws reported that the laws had negative effects on themselves, their teaching, or their students.119 According to NAfME, “Most affected participants stated that [the laws] restricted curriculum and the topics that could be discussed in the music classroom … not because they were breaking the law but because they were afraid of repercussions from students, parents, or administrators misinterpreting the law.” Some teachers reported that out of fear, they had removed almost all content dealing with race. The survey participants also noted that limitations on content had “an adverse impact on their ability to ensure all students are heard, seen, and feel they belong in the music classroom.”120

Researchers conducting focus groups with current and prospective educators in Tennessee during the 2021–2022 school year found that the state’s divisive concepts law, which went into effect that school year, had “significant effects on classrooms, with teachers feeling the need to restrict the ways their teaching engaged with issues of race, racism, and other forms of oppression.” Teachers were unsure how to interpret vague language in the legislation and were afraid of repercussions, and thus expected there to be less frequent instruction about race and racism.121

Outside of individual classrooms, restrictions also inhibit officials’ approval of new policies, programs, and classes. In 2023, North Carolina’s Johnston County School Board adopted a library policy that expanded SB 49’s language to define “curriculum” as applying not just to classroom materials but also to library books. It also extended the ban on instruction on gender identity and sexuality to fifth grade, beyond the legally mandated K–4 ban,122 stating that the ban would otherwise be too difficult to implement in an elementary school that went up to fifth grade.123

Records obtained by American Oversight suggest that after Florida’s 2022 passage of HB 1467, the law mandating review of books for prohibited content, school officials in Escambia County were reluctant to start a program that would have made it easier for students to check out books from their local library through their school library.xxx That August, the school board’s general counsel emailed the Florida School Board Attorneys Association Google group seeking clarification about a proposed memorandum of understanding for the new program. An attorney for another school board counseled against starting the program, stating it would be seen as an attempt to circumvent the law. Another attorney agreed: “I would be very reluctant to enter into such a program now … and ultimately, if a student gets the book from school, you are faced with whether you ‘otherwise made available an inappropriate book.’”xxxi

In Orange County, Florida, public records show school officials struggled to assess books using the vague legal definitions in HB 1467 and the state’s “Don’t Say Gay” law (HB 1557) and adopted restrictive policies to protect teachers from potential penalties for violations. In May 2022, a committee met and discussed Gender Queer: A Memoir, an autobiographical comic geared to teenagers that contains information about sex and sexuality. The meeting minutes show that committee members debated terms in the laws such as “developmentally appropriate,” “age appropriate,” and “pornography,” and ultimately voted to place the book in the media center’s “professional collection” intended for adults at the school.xxxii As one school official said during the meeting: “[I] don’t want to be associated with book banning, but at the end of the day” maintaining students’ access to the book could “have fallout effects for the people who are supplying this book to high school students.”xxxiii

Similar reasoning was used to explain the Arkansas Department of Education’s 2023 decision to remove the pilot AP African American Studies course from its approved course list. “Without clarity, we cannot approve a pilot that may unintentionally put a teacher at risk of violating Arkansas law,” the department said regarding its decision.xxxiv, 124

While rare, some educators have indeed faced grave consequences for violations. A teacher in Duval County, Florida, was removed from classroom duties for displaying a Black Lives Matter flag and face masks criticizing Robert E. Lee.125 In Cobb County, Georgia, teacher Katie Rinderle was fired for reading My Shadow Is Purple, a children’s book about gender stereotypes and being true to oneself, to her fifth grade class.126

In their attempts to comply with vaguely defined restrictions, teachers and administrators must spend considerable effort and time in determining for themselves the bounds of what is permitted. Fearing reprisal, wary educators hesitate to approve new programs or courses, and teachers adhere to the most expansive interpretations of what should be avoided, severely limiting what students can learn.

Denying Students a Full Education

The consequences of this chilling effect are clear: Discussions of important ideas and topics are suppressed, a diverse range of experiences and identities are sidelined, and students’ understanding of history is whitewashed, sanitized, and unchallenged. The denial of enriching context that could inform students’ understanding of themselves and the world around them is particularly apparent in book removals and in education agencies’ curriculum reviews that excise information considered objectionable.

Some of the most egregious examples of this censorship come from Florida. For example, in 2023, the Florida Department of Education rejected the textbook The African American Experience — which contained information about George Floyd’s murder and the 2017 “Unite the Right” white supremacist rally in Charlottesville — without providing an explanation for the rejection.127 Public records obtained by American Oversight reveal that in 2024, in response to the anti-indoctrination HB 7, Orange County Public Schools administrators eliminated a sentence from a Black History Month proclamation that said, “[M]ore than 150 years after slavery was abolished in this nation, our society is still grappling with racial inequality and injustice as we strive toward a more perfect union.”xxxv School administrators had included an almost identical sentence in the previous three years’ proclamations.128 Additionally, in a February 2024 email chain among Orange County school officials about HB 7, one official wrote that it was important that a facilitator, who had offered a group student mentorship program, “understands that nothing [taught] can talk about social justice, implicit bias, or the existence of racism.”xxxvi

In January 2023, Gov. Ron DeSantis announced the state would reject the proposed AP African American Studies course for including “political” content such as “intersectionality and activism” and “Black queer studies.”129 The College Board later removed from its suggested national curriculum several Black authors and made optional previously mandatory content elements such as discussion of the Black Lives Matter movement, denying the changes were in response to pressure from Florida.130

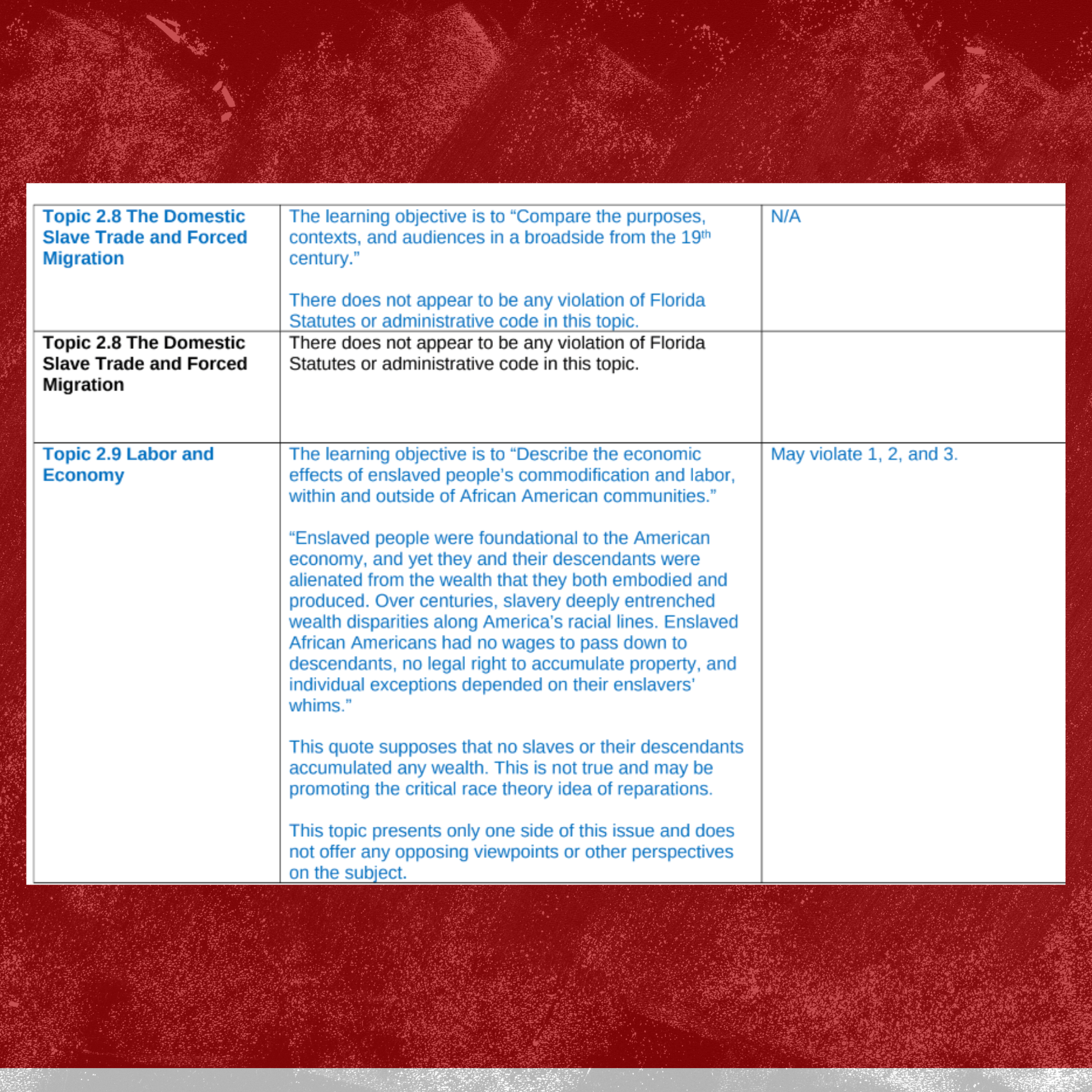

Records obtained by American Oversight contain internal comments from the Florida Department of Education’s review of the rejected curriculum, which included objections to lessons about slavery and racial disparities that reviewers claimed were lacking in “opposing viewpoints.”131, xxxvii Reviewers sought to minimize the horrors and long-term effects of slavery and systemic racism, including by calling for the inclusion of more than “one side of this issue.”xxxviii In response to a lesson stating that “Enslaved African Americans had no wages to pass down to descendants, no legal right to accumulate property, and individual exceptions depended on their enslavers’ whims,”xxxix a reviewer wrote that the passage “supposes that no slaves or their descendants accumulated any wealth,” which “is not true and may be promoting the critical race theory idea of reparations.” The review took issue with the use of the term “enslavers” instead of “owners” and suggested that several references to the year 1619 “may be intended to promote ‘the 1619 Project’s’ flawed view that 1619 is the real start date for American History.”xl A discussion of how Europeans benefited from the slave trade prompted a reviewer to warn that the topic “may lead to a viewpoint of a ‘oppressor vs. oppressed’ based solely on race or ethnicity.”xli And a course unit on the origins of the transatlantic slave trade was criticized for not sufficiently addressing “the internal slave trade/system within Africa” or mentioning the “role, if any, played by continental Africans.”xlii

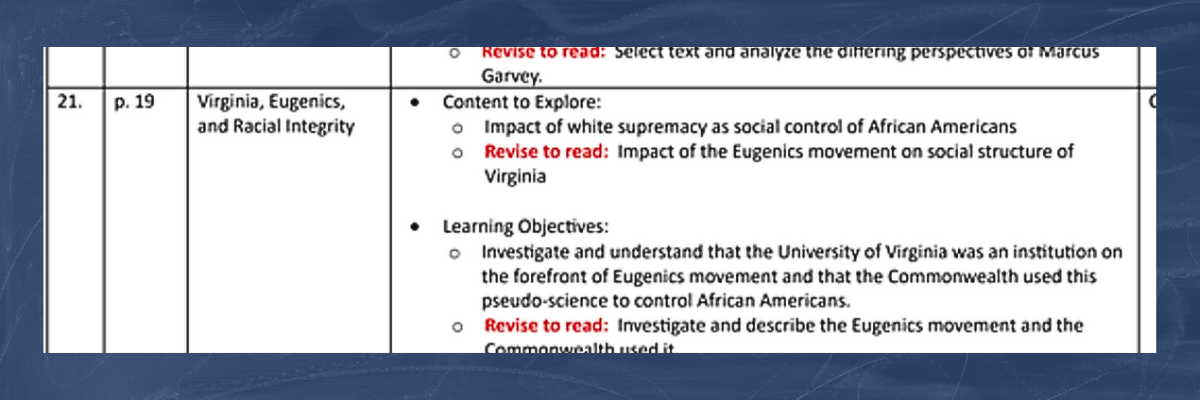

Public records reveal a similar discomfort with historical truths in the Virginia Department of Education’s review of the state’s African American history elective course, which had been developed by the previous administration and a committee of experts. The department prepared a list of “suggested revisions” to help the course comply with the order, which included removing the claim that eugenics is pseudoscience and that the “Lost Cause” myth about the Civil War continues to influence U.S. society.132, xliii Another suggestion paraphrased Martin Luther King Jr.’s criticism of “white moderates” for being the “great stumbling block in [the] stride toward freedom” to only mention “moderates.”xliv, 133

Removal of instructional materials and suppression of critical ideas has played out in other states. In Tennessee, fears over the state’s censorship laws pushed event organizers to alter a school presentation by the authors of a Pulitzer Prize–winning book about George Floyd,134 telling the authors not to go into depth about systemic racism. In Oklahoma, the State Department of Education launched an investigation into a school for teaching the book Dear Martin, a novel about a Black child killed after an encounter with a white off-duty police officer.135 In Arkansas, Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders’ vague anti-CRT executive order led the state Department of Education’s review of the Arkansas Governor’s School Curriculum to flag mentions of race, same-sex couples, non-native English speakers, and sustainability initiatives. A story about a Vietnamese monk was flagged for potential violation for “highlighting nationality and religion,”xlv and a 2012 National Education Association video on non-native English instruction was flagged for showing the “lived experience of English learners” while providing a “negative portrayal of unprepared educator[s].”136, xlvi

Some school districts have gone so far as to interpret “divisive concepts” laws in broad ways that effectively prohibit materials with LGBTQ+ characters.137 For instance, officials reviewing Title IX instructional materials for compliance flagged some items for containing a “potential LGBTQ+ interpretation.”138 Children’s books such as Red: A Crayon’s Story and Odd Velvet were flagged for the same reason, as was a Sesame Street video about bullying.139 A presentation on Title IX for high school students was also flagged because a slide about flirting and harassment included an image of two women holding hands.xlix So was a slide on “Bystander Intervention” in another Title IX presentation, presumably because it included an image of one woman hugging another.xlviii

Bans on sexual orientation or gender identity content have been used to target symbols such as the pride flag, display of which one North Carolina education advocate had advised was a legal “gray area.”li In 2023, the Arkansas Department of Education circulated a list of incidents that violated the state’s executive order, including displaying the pride flag because it was a “politicized symbol” that “gives students the impression that only one outlook on gender and sexuality is acceptable in schools.”140

As the Campaign for Southern Equality noted in a Title IX complaint arguing that the implementation of North Carolina’s SB 49 and HB 574 — which bans transgender girls from participating in girls’ sports141 — results in anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination:

[The] mandates to enforce SB49 and HB574 have already created a hostile educational environment on the basis of sex in North Carolina public schools. Their guidance, or[The] mandates to enforce SB49 and HB574 have already created a hostile educational environment on the basis of sex in North Carolina public schools. Their guidance, or lack thereof, on SB49 has already forced the involuntary outing of transgender students as well as walling LGBTQ students off from supportive materials, services, and educators. And their approach to HB574 further marginalizes transgender students by barring transgender girls from competing for their schools and jeopardizing the ability of transgender boys to do so.142

The Campaign for Southern Equality is not alone in this assessment of the discriminatory nature of SB 49 and similar laws in other states. In May 2024, the National Women’s Law Center filed Title IX complaints with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights alleging that school districts in Cobb County, Georgia, and Collier County, Florida, engaged in illegal discrimination on the basis of sex, race, and nationality when they censored books and curriculum regarding LGBTQ+ people and people of color.143 According to the North Carolina-based Education Justice Alliance:

The implementation of SB 49 exacerbates systemic inequities within our education system by selectively silencing the experiences and identities of LGBTQ students and families. This legislation not only marginalizes vulnerable communities but also undermines the inclusive and affirming learning environments that all students deserve. Lawmakers across the country are using exclusionary strategies to craft these types of discriminatory bills in a collective effort to dismantle the last public good we have in this country.144

The examples outlined in this report — of confusion and fear, stifling caution and overt censorship — paint a picture of a nationwide pattern: vaguely worded laws and executive orders drafted by politicians, not education experts or historians, lead to widespread uncertainty about legal definitions, ultimately producing a chilling effect that directly impacts what students can learn and how they express themselves.

IV. The End Game: A Far-Right Alternative to Public Schools

The far right’s attack on public education did not start — and will not end — with “divisive concepts” measures and the chaos and confusion they have wrought. In fact, the movement has tied the spread of state-level bans to its longstanding campaign to defund public education in favor of private school vouchers and publicly funded charter schools, including those in the Hillsdale network. In September 2021, senior officials at the Heritage Foundation and the Educational Freedom Institute published a blog post arguing that the school choice movement needed to embrace a “values-based appeal” as part of a new strategy to increase the success of their national campaign.145 The authors claimed that families, elected leaders, and other stakeholders could be persuaded to support private school vouchers and publicly funded charter schools if they were told that such programs would enable them to “reject curriculum they do not like, such as Critical Race Theory and the 1619 Project.”146 According to its proponents, this strategy is succeeding. In February 2023, Heritage Foundation officials concluded that a “key explanation for the current success of the school-choice movement is a switch in political strategy among some of its influential leaders.”147 According to Heritage Foundation president Kevin Roberts, “We don’t merely seek an exit from the system; we are coming for the curriculums and classrooms of the remaining public schools, too.”148

Officials across the country responsible for overseeing public education have bought into this narrative that schools have failed families and students through indoctrination. One notable example is Oklahoma State Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters, a far-right firebrand who has leveraged opposition to supposed “divisive concepts” to argue for shifting funds away from public education. While attending the 2024 Republican National Convention, Walters shared in an interview that eliminating “woke indoctrination” from schools and establishing universal school choice were top priorities.149

If far-right actors like Walters and the Heritage Foundation succeed, problematic alternatives to public education already developing at the state level could become national policy. Arizona’s Empowerment Scholarship Account, a universal education savings account program, provides a case in point. The program allows parents to access public funding to spend on private schools, including religious academies that require adherence to particular faiths.150 According to a Brookings Institution study, the program has disproportionately benefited wealthy families with high levels of educational attainment.151

Project 2025, the policy agenda created by the Heritage Foundation and more than 100 other right-wing organizations for a second Trump administration, draws heavily on Arizona’s model152 and could nationalize the program’s disparate impacts. Lindsey Burke, the director of the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy and author of Project 2025’s education chapter, recommends replacing the Department of Education’s Title I program, which supports schools that serve a disproportionate number of low-income students, with direct block grants for states to shore up charter funding and vouchers.153

As anti-public education advocates and for-profit interests pave the way for billions of dollars in public funding to be diverted from public education budgets to private religious schools and ideologically aligned charter networks,154 private business interests like educational tech companies, curriculum consultants, and other vendors will likely profit immensely from newly available money. Potential profiteers include U.S. Rep. Byron Donalds of Florida and his wife, Erika Donalds, the founder of OptimaEd, a self-described “education experience company” that provides “virtue-based classical education” through charter and other non-public school options.155 Optima Academy Online, Erika Donalds’ K-12 virtual-reality online school, shares the focus on “classical education” that Hillsdale popularized in far-right education circles. Prior to founding OptimaEd, Donalds served on the board of Mason Classical Academy, a formerly Hillsdale-affiliated school in Naples, Florida.156 Her charter-planting nonprofit Optima Foundation is linked to Hillsdale College.157 American Oversight obtained documents showing that Donalds participated in a 2022 Heritage Foundation event unveiling its Education Freedom Report Card,158 during which she sat on a panel entitled “Putting Education Choice Into Action.” The discussion came immediately after a panel featuring Lindsey Burke and preceded remarks by Kevin Roberts and Gov. Ron DeSantis.lii In 2023, Donalds joined the Heritage Foundation as a visiting fellow on education freedom.157

As activists claim public schools are failing families, they are doing everything in their power to bring that outcome about. The end game is not rejuvenating the U.S.’s public education system, but gutting it and replacing it with a system that serves ultra-conservative political, financial, and cultural interests.

V. Conclusion

Lurking behind these “divisive concepts” laws, book purges, and curriculum reviews is a nefarious idea: Public schools are dangerous places that harm children, in which teachers eagerly indoctrinate the young with leftist political ideas.

Through this distorted prism, a book about a child embracing their unique identity is not about empathy and acceptance; instead, as one Georgia parent said in an email obtained by American Oversight, it’s a “garbage agenda” being “pushed” on students.liii New curriculum — created or adopted amid the once-in-a-generation racial justice protests and a global pandemic that disproportionately impacted people of color, and designed to explain how racial inequality interacts with current policies and systems — is not relevant educational information, but rather a plot to “inundate every classroom with material that is specifically African American-centric”liv and “destroy” the nation.160 William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Antony and Cleopatra are not cherished classics ripe for ever-evolving interpretation, but rather are inappropriate plays that should be culled from curriculum.lv Even the mention in a math textbook of a tropical storm on the other side of the globe could be censored.lvi

These inaccurate and harmful ideas have led to real-world policy. The first Trump administration’s promotion of its “1776 Report” trumpeted the greatness of America and denied any hint of an unjust past, leading state lawmakers who were keen to beef up their ideological credentials to pass laws banning the teaching of “divisive concepts,” employing vague language that could encompass nearly anything contrary to a narrow, right-wing worldview. Now, a second Trump administration is already taking steps to elevate this agenda to national policy.161

This report uses documents obtained from dozens of public records requests to demonstrate how the deluge of restrictions creates confusion for state education institutions, administrators, and teachers. The records show educators’ uncertainty and desire for clarity. Lurking behind each inquiry is the implicit fear: Will I get fired if I teach my students this lesson? These “divisive concepts” laws have been so effective at scaring teachers that many teachers cautiously removed any potentially offending material, avoiding lessons that discuss people who are not heterosexual, white, Christian, or American. This censorship further entrenches systemic inequalities and risks leaving students of different backgrounds feeling invisible or unaccepted. Collapsing the range of what students are exposed to denies them the full education that every child in America has the right to, and does little to prepare them to navigate and meaningfully participate in a multicultural world with diverse viewpoints.

The harmful effects of this attack on public education do not end with censorship. Many of the activists and officials pushing “divisive concepts” measures are linked to efforts to divert public education money to private interests and move students to schools run by private companies, including those centered on far-right or religious teachings.

Our democracy is only as strong as the systems that hold it together and help it function. Public schools represent a vital democratic institution thanks to their role in ensuring an informed and engaged electorate, and the health of our society depends on the ability of our public schools to represent and serve the full range of our nation and its people.

Records Obtained by American Oversight

i NC-MECKLENBURG-23-1188-B: “Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, N.C., Records Related to Content Determined Prohibited by SB 49,” 210, received by American Oversight February 14, 2024.

ii FL-DOE-22-0431-A: “Florida Education Department Records Released in Response to Request for Communications with Math Textbook Publishers,” 3429-3439, received by American Oversight February 9, 2022.

iii AR-DOE-23-0823-A: “Arkansas Department of Education Records Regarding the Rejection of AP African American Studies,” 4–34, received by American Oversight October 25, 2023.

iv VA-DOE-24-0011-A: “Virginia Department of Education Records from Review of African American History Elective Course,” 2-9, received by American Oversight March 18, 2024.

v VA-DOE-22-0316-B: “Virginia Department of Education Records Regarding Email Communications About Tip Line,” 1179, received by American Oversight May 12, 2022.

vi VA-DOE-22-0316-B: “Virginia Department of Education Records Regarding Email Communications About Tip Line,” 1154.

vii FL-GOV-23-0182-A: “Florida Governor’s Office Communications” 1015, 1029, 1037, received by American Oversight April 5, 2024.

viii NC-MECKLENBURG-23-1247-A: “Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, N.C., Communications Regarding Senate Bill 49,” 315, received by American Oversight February 14, 2024.

ix NC-MECKLENBURG-23-1247-A: “Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, N.C., Communications Regarding Senate Bill 49,” 807.

x NC-MECKLENBURG-23-1247-A: “Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, N.C., Communications Regarding Senate Bill 49,” 62-79.

xi NC-ROCKINGHAM-23-1245-A: “Rockingham County Schools, N.C., Communications Regarding the Implementation of Senate Bill 49,” 290, received by American Oversight January 10, 2024.

xii NC-ROCKINGHAM-23-1245-A: “Rockingham County Schools, N.C., Communications Regarding the Implementation of Senate Bill 49,” 3.

xiii NC-ROCKINGHAM-23-1245-A: “Rockingham County Schools, N.C., Communications Regarding the Implementation of Senate Bill 49,” 5.

xiv NC-ROCKINGHAM-23-1245-A: “Rockingham County Schools, N.C., Communications Regarding the Implementation of Senate Bill 49,” 358.

xv FL-BREVARD-23-1239-A: “Brevard Public Schools, Fla., Communications Regarding the Implementation of the Stop W.O.K.E. Act,” 178, received by American Oversight June 10, 2024.

xvi FL-BREVARD-23-1239-A: “Brevard Public Schools, Fla., Communications Regarding the Implementation of the Stop W.O.K.E. Act,” 178.

xvii FL-BREVARD-23-1239-A: “Brevard Public Schools, Fla., Communications Regarding the Implementation of the Stop W.O.K.E. Act,” 178.

xviii VA-DOE-22-0316-A: “Virginia Department of Education Records Regarding Email Communications About Tip Line,” 930, received by American Oversight May 5, 2022.

xix VA-DOE-22-0316-A: “Virginia Department of Education Records Regarding Email Communications About Tip Line,” 993.

xx NC-MECKLENBURG-23-1188-B: “Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, N.C., Records Related to Content Determined Prohibited by SB 49,” 301.

xxi NC-MECKLENBURG-23-1188-B: “Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, N.C., Records Related to Content Determined Prohibited by SB 49,” 210.

xxii FL-DOE-22-0431-A: “Florida Education Department Records Released in Response to Request for Communications with Math Textbook Publishers,” 1010-1012.

xxiii FL-DOE-22-0431-A: “Florida Education Department Records Released in Response to Request for Communications with Math Textbook Publishers,” 1010-1012.

xxiv FL-DOE-22-0431-A: “Florida Education Department Records Released in Response to Request for Communications with Math Textbook Publishers,” 1012.

xxv FL-DOE-22-0431-A: “Florida Education Department Records Released in Response to Request for Communications with Math Textbook Publishers,” 1011.

xxvi FL-DOE-22-0431-A: “Florida Education Department Records Released in Response to Request for Communications with Math Textbook Publishers,” 1011.

xxvii FL-DOE-22-0431-A: “Florida Education Department Records Released in Response to Request for Communications with Math Textbook Publishers,” 3440.

xxviii FL-DOE-22-0431-A: “Florida Education Department Records Released in Response to Request for Communications with Math Textbook Publishers,” 3436.

xxix FL-DOE-22-0431-A: “Florida Education Department Records Released in Response to Request for Communications with Math Textbook Publishers,” 3429.

xxx FL-SARASOTA-23-0313-A: “Sarasota County, Fla., Public Schools for Documents Concerning Book Bans,” 1200, received by American Oversight July 31, 2023.

xxxi FL-SARASOTA-23-0313-A: “Sarasota County, Fla., Public Schools for Documents Concerning Book Bans,” 1200.

xxxii FL-ORANGE-23-0318-A: “Orange County, Fla., Public Schools Documents Concerning Book Bans,” 36-40, received by American Oversight May 9, 2023.

xxxiii FL-ORANGE-23-0318-A: “Orange County, Fla., Public Schools Documents Concerning Book Bans,” 38.

xxxiv AR-DOE-23-1258, 23-1259-A: “Arkansas Department of Education Records Regarding the Rejection of AP African American Studies,” 1-2, received by American Oversight December 29, 2023.

xxxv FL-ORANGE-24-0546-A: “Orange County Public Schools, Fla., Communications Regarding the Implementation of the Stop W.O.K.E. Act,” 3391, received by American Oversight July 3, 2024.

xxxvi FL-ORANGE-24-0546-A: “Orange County Public Schools, Fla., Communications Regarding the Implementation of the Stop W.O.K.E. Act,” 3263.

xxxvii FL-DOE-23-0158-A: “Florida Department of Education Records Regarding AP African American Studies,” 15, received by American Oversight June 13, 2023.

xxxviii FL-DOE-23-0158-A: “Florida Department of Education Records Regarding AP African American Studies,” 15-22.

xxxix FL-DOE-23-0158-A: “Florida Department of Education Records Regarding AP African American Studies,” 23.

xl FL-DOE-23-0158-A: “Florida Department of Education Records Regarding AP African American Studies,” 32.

xli FL-DOE-23-0158-A: “Florida Department of Education Records Regarding AP African American Studies,” 19.

xlii FL-DOE-23-0158-A: “Florida Department of Education Records Regarding AP African American Studies,” 15.

xliii VA-DOE-24-0011-A: “Virginia Department of Education Records from Review of African American History Elective Course,” 1.

xliv VA-DOE-24-0011-A: “Virginia Department of Education Records from Review of African American History Elective Course,” 11.

xlv AR-DOE-23-0823-A: “Arkansas Department of Education Records Regarding the Rejection of AP African American Studies,” 4–34, received by American Oversight October 25, 2023.

xlvi AR-DOE-23-0823-A: “Arkansas Department of Education Records Regarding the Rejection of AP African American Studies,” 4–34.

xlvii NC-MECKLENBURG-23-1188-A: “Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, N.C., Records Related to Content Determined Prohibited by SB 49,” 3, received by American Oversight January 30, 2024.

xlviii NC-MECKLENBURG-23-1188-A: “Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, N.C., Records Related to Content Determined Prohibited by SB 49,” 3.

xlix NC-MECKLENBURG-23-1188-A: “Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, N.C., Records Related to Content Determined Prohibited by SB 49,” 3.

l NC-MECKLENBURG-23-1188-A: “Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, N.C., Records Related to Content Determined Prohibited by SB 49,” 3.

li NC-ROCKINGHAM-23-1245-A: “Rockingham County Schools, N.C., Communications Regarding the Implementation of Senate Bill 49,” 290.

lii FL-DOE-23-0882-A: “Florida Department of Education Communications With and About Erika Donalds,” 288-290, received by American Oversight March 7, 2024.

liii GA-COBB-23-1175-A: “Cobb County School District, Ga., Records of Reviews Identifying Curriculum Materials Containing ‘Divisive Concepts’,” 97, received by American Oversight January 22, 2024.

liv VA-DOE-22-0316-A: “Virginia Department of Education Records Regarding Email Communications About Tip Line,” 10.

lv GA-COBB-23-1175-A: “Cobb County School District, Ga., Records of Reviews Identifying Curriculum Materials Containing ‘Divisive Concepts’,” 1595.

lvi FL-DOE-22-0431-A: “Florida Education Department Records Released in Response to Request for Communications with Math Textbook Publishers,” 3440, received by American Oversight February 9, 2023.

Endnotes

1 Jeffrey Adam Sachs and Jeremy C. Young, “America’s Censored Classrooms 2024,” PEN America, October 8, 2024, https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms-2024/.

2 “The 2024 Republican Platform,” Republican National Committee, 2024, https://prod-static.gop.com/media/RNC2024-Platform.pdf?_gl=1*18ov8ne*_gcl_au*NjMwODYwMzI2LjE3MzgwOTY2NTk.&_ga=2.25192894.2002610613.1738096660-2078657243.1738096660.

3 Lindsey M. Burke, “Department of Education,” in Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise, 2023, https://static.project2025.org/2025_MandateForLeadership_CHAPTER-11.pdf.

4 Juan Perez Jr. and Mackenzie Wilkes, “Trump issues orders on K-12 ‘indoctrination,’ school choice and campus protests,” Politico, January 29, 2025, https://www.politico.com/news/2025/01/29/trump-k12-indoctrination-school-choice-campus-protests-education-00201235.

5 Leah Watson, “What the Fight Against Classroom Censorship Is Really About,” American Civil Liberties Union, September 7, 2023, https://www.aclu.org/news/free-speech/what-the-fight-against-classroom-censorship-is-really-about; Jonathan Friedman, James Tager, and Andy Gottlieb, “Educational Gag Orders: Legislative Restrictions on the Freedom to Read, Learn, and Teach,” PEN America, November 8, 2021, https://pen.org/report/educational-gag-orders/.

6 Riham Feshir, “As schools promise racial equity, the path forward is often met with resistance,” Minnesota Public Radio, October 7, 2020, https://www.mprnews.org/story/2020/10/06/as-schools-promise-racial-equity-the-path-forward-is-often-met-with-resistance; Linday McKenzie, “Words Matter for College Presidents, but So Will Actions,” Inside Higher Ed, June 7, 2020, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/06/08/searching-meaningful-response-college-leaders-killing-george-floyd; Stephen Sawchuk, “4 Ways George Floyd’s Murder Has Changed How We Talk About Race and Education,” EducationWeek, April 21, 2021, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/4-ways-george-floyds-murder-has-changed-how-we-talk-about-race-and-education/2021/04.

7 Niedzwiadek, “Trump Goes after Black Lives Matter, ‘Toxic Propaganda’ in Schools.”

8 Laura Meckler and Josh Dawsey, “Republicans, Spurred by an Unlikely Figure, See Political Promise in Targeting Critical Race Theory,” Washington Post, June 21, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2021/06/19/critical-race-theory-rufo-republicans/; “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping,” Executive Office of the President, September 28, 2020, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/28/2020-21534/combating-race-and-sex-stereotyping.

9 “Executive Order on Establishing the President’s Advisory 1776 Commission,” The White House, November 2, 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20201102195342/https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-establishing-presidents-advisory-1776-commission/; The President’s Advisory 1776 Commission, “The 1776 Report,” The White House, January 18, 2021,

10 “PEN America Index of Educational Gag Orders,” PEN America, accessed January 28, 2025, https://airtable.com/appg59iDuPhlLPPFp/shrtwubfBUo2tuHyO/tbl49yod7l01o0TCk/viw6VOxb6SUYd5nXM?blocks=hide; Sachs and Young, “America’s Censored Classrooms 2024.”

11 “In the Documents: North Carolina Educators Scramble to Comply with State’s ‘Don’t Say Gay’ Law,” American Oversight, April 11, 2024, https://www.americanoversight.org/in-the-documents-north-carolina-educators-scramble-to-comply-with-states-dont-say-gay-law.

12 “Florida Dept. of Education Emails Reveal Confusion for Textbook Companies, New Examples of Lesson Changes,” American Oversight, July 26, 2023, https://www.americanoversight.org/florida-dept-of-education-emails-reveal-confusion-for-textbook-companies-new-examples-of-lesson-changes.

13 “Inside the Virginia Education Department’s Review of African American History Course,” American Oversight, June 26, 2024, https://www.americanoversight.org/inside-the-virginia-education-departments-review-of-african-american-history-course.

14 “America First vs. America Last Report Card: U.S. History,” America First Policy Institute, October 11, 2024, https://americafirstpolicy.com/issues/america-first-vs-america-last-report-card-u.s-history; Zachary Schermele, “Where does Linda McMahon, Trump’s education secretary nominee, stand on key issues?” USA Today, December 5, 2024, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2024/12/02/linda-mcmahon-trump-education/76448914007/.

15 Friedman, Tager, and Gottlieb, “Educational Gag Orders: Legislative Restrictions on the Freedom to Read, Learn, and Teach.”

16 Tucker Carlson, “Tucker Carlson: Cultural Revolution has come to America – brainwashing underway” Fox News, June 6, 2020,

https://www.foxnews.com/opinion/cults-allies-george-floyd-tucker-carlson.

17 Niedzwiadek, “Trump Goes after Black Lives Matter, ‘Toxic Propaganda’ in Schools.”

18 Sarah Mervosh and Dana Goldstein, “Chris Rufo calls on Trump to end critical race theory ‘cult indoctrination’ in federal government,” Fox News, September 1, 2020, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/chris-rufo-race-theory-cult-federal-government.

19 Matthew S. Schwartz, “Trump Tells Agencies to End Trainings on ‘White Privilege’ and ‘Critical Race Theory,’” NPR, September 5, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/09/05/910053496/trump-tells-agencies-to-end-trainings-on-white-privilege-and-critical-race-theor.

20 Nicole Gaudiano, “Trump creates 1776 Commission to promote ‘patriotic education,” Politico, November 2, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/11/02/trump-1776-commission-education-433885.