When the Government Uses Redactions to Hide Evidence of Wrongdoing

Here are four reasons executive privilege should not apply to communications about misconduct.

The investigation into and the aftermath of the Trump administration’s Ukraine pressure campaign revealed a number of ways top officials sought to hide their actions from public view — from Rudy Giuliani’s secret backchannel and the shadow foreign policy of the “three amigos” to the administration’s total obstruction of the impeachment inquiry itself.

Last week, American Oversight joined the fight against another, less-flashy method the administration has used to keep the public in the dark: the misuse of FOIA redactions to hide evidence of government wrongdoing.

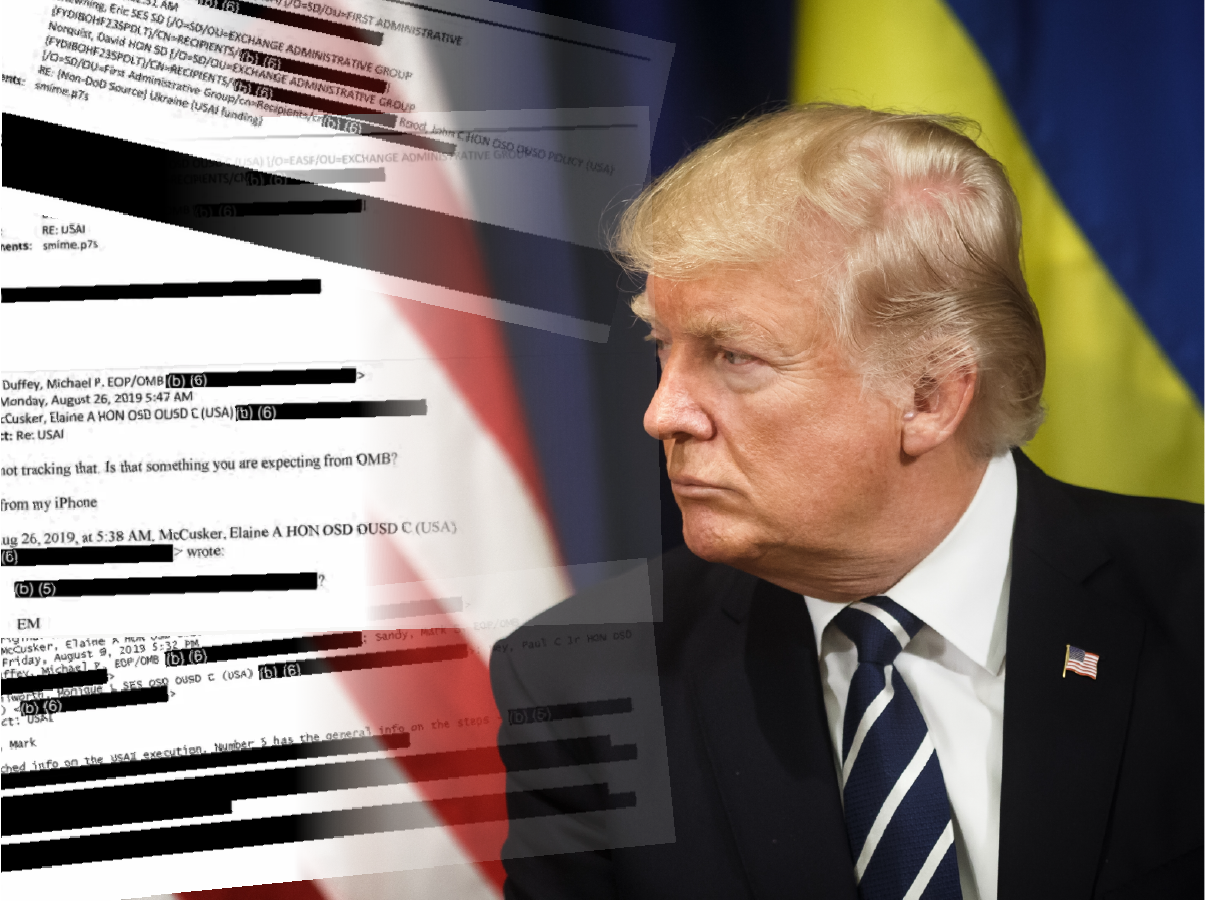

Ukraine-related documents released to the Center for Public Integrity (CPI) in December included a number of redactions — redactions later revealed to be discussions about the illegal withholding of aid to Ukraine.

The Justice Department maintains that much of the obscured information is protected under the “presidential communications privilege” and the “deliberative process privilege.” CPI is challenging those claims in federal court, and last week American Oversight along with Democracy Forward filed an amicus brief in support of CPI’s challenge.

The documents obtained by CPI through the Freedom of Information Act showed communications between the Defense Department and the White House’s Office of Management and Budget about the holdup in congressionally approved security assistance to Ukraine, which President Donald Trump was using to coerce that country into announcing an investigation into presidential candidate Joe Biden. The pages were heavily blacked out, but in early January, the website Just Security revealed that the redactions had hidden explicit warnings from the Pentagon’s top budget officer that the freeze would violate the law — warnings OMB’s general counsel said in December he had never been given. On Jan. 16, the Government Accountability Office released a report finding that this freeze was, in fact, illegal.

But detailed contents of many of the documents remains obscured, thanks to the Trump administration’s presidential and deliberative privilege claims. As American Oversight’s amicus brief lays out, however, many of these privilege claims are just wrong, especially because evidence of governmental wrongdoing is not privileged information. Here’s why:

1. The Presidential Communications Privilege can only be applied to inter-agency communications in limited circumstances — and this doesn’t pass the test.

The presidential communications privilege is narrowly limited to ensure the president’s decisions are informed by candid and honest advice, and it typically only applies to communications that directly involve the president, vice president, or senior White House advisers. But most, if not all, of the redactions in this case only involve Defense and OMB officials, not any White House officials.

The defendants in the case, the Defense Department and OMB, have not established that these communications meet the very limited circumstances in which the presidential privilege can apply to such internal or inter-agency contacts. Extending the privilege to these communications would require the agencies to show that the records capture advice that was actually communicated to the president or a senior adviser. Instead, Defense describes the records as merely including “references to communications involving the President.” This weak justification raises serious questions about the Trump administration’s redaction of many of these emails.

2. Agency directives, actions and the reasons for them don’t fall under the Deliberative Process Privilege.

The deliberative process privilege, which exempts “give and take” or pre-decisional communications used in helping an official arrive at said decision, also cannot be applied here. These records appear to contain information about agency guidance, directives and related justifications — which by their final nature are not “pre-decisional.” The unredacted portions of the records reflect discussions of how to implement decisions that had already been made. In fact, OMB has said that the discussion included in the documents addresses “how best to execute a series of short-term budgetary apportionment actions.” And apportionment actions follow final decisions.

3. The Deliberative Process Privilege also cannot apply to misconduct.

The documents directly relate to the unlawful withholding of funds appropriated by Congress, a violation of the 1974 Impoundment Control Act. Moreover, evidence and testimony made public during the House’s impeachment inquiry indicates that this freeze was done in furtherance of Trump’s scheme to get Ukraine to help him politically. Many courts have held that the deliberative process privilege doesn’t apply to government misconduct or illegal actions.

As American Oversight and Democracy Forward’s brief argues, the deliberative process privilege “is not intended to ensure candor when government actors are deliberating over how to break the law. It is not a co-conspirators’ privilege,” and if there is reason to believe deliberations involve official misconduct, the privilege “disappears altogether.” Revealing such misconduct serves the public interest in “honest, effective government,” an interest that in this case outweighs any executive privilege.

4. The president also does not get a pass to cover up his participation in the misconduct.

Like the deliberative process privilege, the presidential communications privilege is intended to protect officials’ ability to supply candid advice without the fear of disclosure. But communications about misconduct or illegal actions — especially when the president is personally involved — are not legitimate protected advice, and such communications should be disclosed to the public. Here, there is substantial evidence that Trump himself was directly and personally involved in the decision to withhold Ukraine security assistance.

“When the public is still in the dark about many details of the president’s Ukraine scheme, this is an all-hands-on-deck moment for transparency,” said Austin Evers, American Oversight’s executive director. “Governmental privileges cannot become a tool to mask misconduct or illegality.”

The length of time it often takes in court to address such overbroad redactions means that agencies can delay making the obscured information public until after a controversy like the Ukraine scandal has passed, even if that information is vital to the public’s understanding of the scandal itself. Improperly applied exemptions don’t just help agencies evade accountability — they undermine the intent of the Freedom of Information Act and the right of the American public to know what its government is doing.