Why Former Ag Secretary Sonny Perdue’s Compliance with Federal Ethics Rules Still Needs to Be Investigated

From disappearing and reappearing assets on his financial disclosures to potentially lucrative business moves, Perdue's big-dollar financial dealings still bear scrutiny.

This week, the Washington Post published a deeply reported article about the financial dealings of former Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue — namely, a little-noticed real estate deal undertaken in the weeks between Perdue’s nomination and his confirmation by the Senate.

As detailed by Post reporter Desmond Butler, Perdue’s former company AGrowStar bought a South Carolina grain plant in February 2017 for a fraction of its estimated value. The transaction, which Perdue was not legally required to disclose prior to his confirmation, raises serious questions not just about his financial disclosures but also about whether the seller, a giant agricultural corporation with a multimillion-dollar lobbying outfit, was looking to extract favorable treatment from the new Trump administration.

But Perdue’s federal ethics agreements have also drawn scrutiny for other reasons. Last October, American Oversight called upon the Agriculture Department’s inspector general to examine Perdue’s disclosures as well as whether the Trump administration took an action that may have earned Perdue millions of dollars. In addition, an examination of his financial disclosures from 2017 through 2019 reveal a number of unexplained oddities, which were also highlighted by the Post.

Here, American Oversight explains how a potential decision by the Army Corps of Engineers while Perdue was serving in the Trump administration could have been a lucrative one for him. We also take a closer look at the federal disclosures from his first three years in office, identifying several financial holdings that disappear one year and reappear the next.

Federal Ethics Disclosures

While January marked the end of an historically corrupt administration in which conflicts of interest abounded, the importance of robust ethics rules for government officials has not diminished. Indeed, the Trump administration made clear the need for transparency when it comes to ensuring that officials are not using government positions to advance their personal interests.

Ethics agreements — and waivers granting officials permission to go around those limits — can reveal key information about potential conflicts or raise important questions about whether those same officials are abiding by the rules. Holding former high-level members of the Trump administration accountable for any self-enrichment or ethics conflicts is an ongoing project that, along with strengthening the federal ethics program, is part of ensuring such abuses of office do not occur in the future.

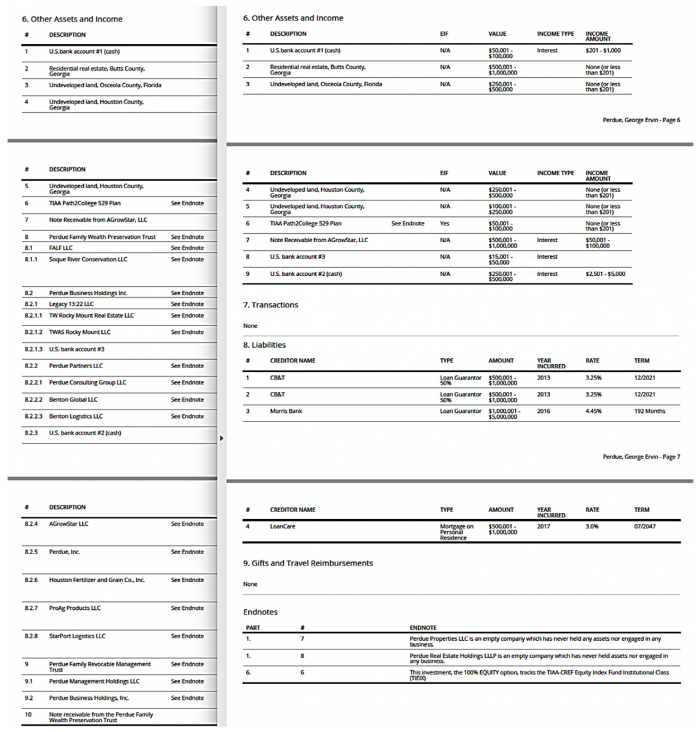

The former governor of Georgia, Perdue entered the Trump administration with a long recusal letter and an extensive financial disclosure report that listed a number of Georgia-based businesses to which he was tied. In October 2020, American Oversight sent a letter to the Department of Agriculture’s Inspector General asking the office to investigate whether Secretary Perdue was violating his ethics agreement with some of his investments. Our request for investigation centered on two basic issues: first, whether Perdue’s holdings violated the plain language of his ethics agreement, and second, whether Perdue played an improper role in an Army Corps of Engineers decision that may have increased the value of one of those holdings, a business called Soque River Conservation LLC, by approximately $3 million.

We asked the inspector general to investigate because, due to the limits of disclosure laws, there is only so much we can know about whether Perdue abided by the ethics agreement he signed when he took office. Below, we outline some of the open questions that we hope the inspector general can answer.

Soque River Conservation

Perdue’s Soque River Conservation transaction has drawn attention because of the specific way a Trump administration decision may have resulted in a significant windfall for Perdue.

In 2009, while governor, Perdue and a business partner bought a plot of land along the Soque River in northern Georgia. That land was ultimately converted to a wetland mitigation bank, which is a system of land preservation where bank credits are granted by the federal government to offset adverse impacts to wetlands in other locations. Perdue and his partner received both wetland and stream credits from the government for turning the land into a wetland preserve, which they could sell to developers.

The wetland credits were far more valuable than the stream credits: In 2019, a Georgia Department of Transportation memo valued the stream credits at a mere $38 each, while wetland credits were valued at $50,000. In 2018, while Perdue was agriculture secretary, his Soque River business partner petitioned the Army Corps of Engineers to convert some of its stream credits to wetland credits. The exchange Soque River Conservation requested — 616.01 stream credits for 59.12 wetland credits — would have increased the value of their credits by approximately $2.9 million using the Transportation Department estimations.

It isn’t clear from the Army Corps’ database how many of the credits were ultimately converted. But the request itself, and the conversions that we know did happen, is highly problematic, given Perdue’s enormous potential financial benefit from a federal government decision and his status as a co-owner of the business. We asked USDA’s inspector general to investigate whether Perdue attempted to influence the Army Corps’ decision, directly or indirectly.

Issues with Perdue’s Ethics Filings

Standing to personally profit off the Soque River decision was not the only concerning detail from Perdue’s ethics filings, however. Perdue seemed to have been in violation of the terms of his ethics agreement, and had assets disappear and reappear from disclosure filings in ways that suggest that either he may have failed to file appropriate transaction reports (he hasn’t filed any) or he may have failed to disclose all of his holdings in 2018. Below are some additional details from Perdue’s ethics filings that we did not include in our letter.

As part of his confirmation proceedings in March 2017, Perdue outlined the steps he would take to avoid ethical questions and conflicts of interest as secretary. (You can read Perdue’s ethics agreement and the rest of his ethics filings referenced here by searching the Office of Government Ethics’ database.) In addition to other actions, Perdue had two trusts that he agreed to “restructure” so that neither Perdue nor his wife would benefit from them. He also agreed that neither he nor his wife would serve as trustees.

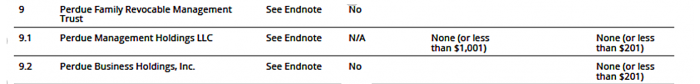

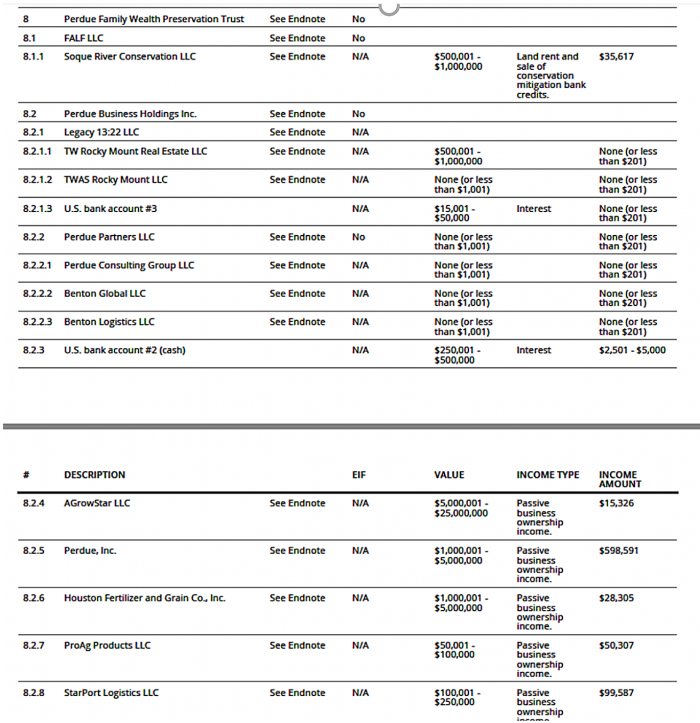

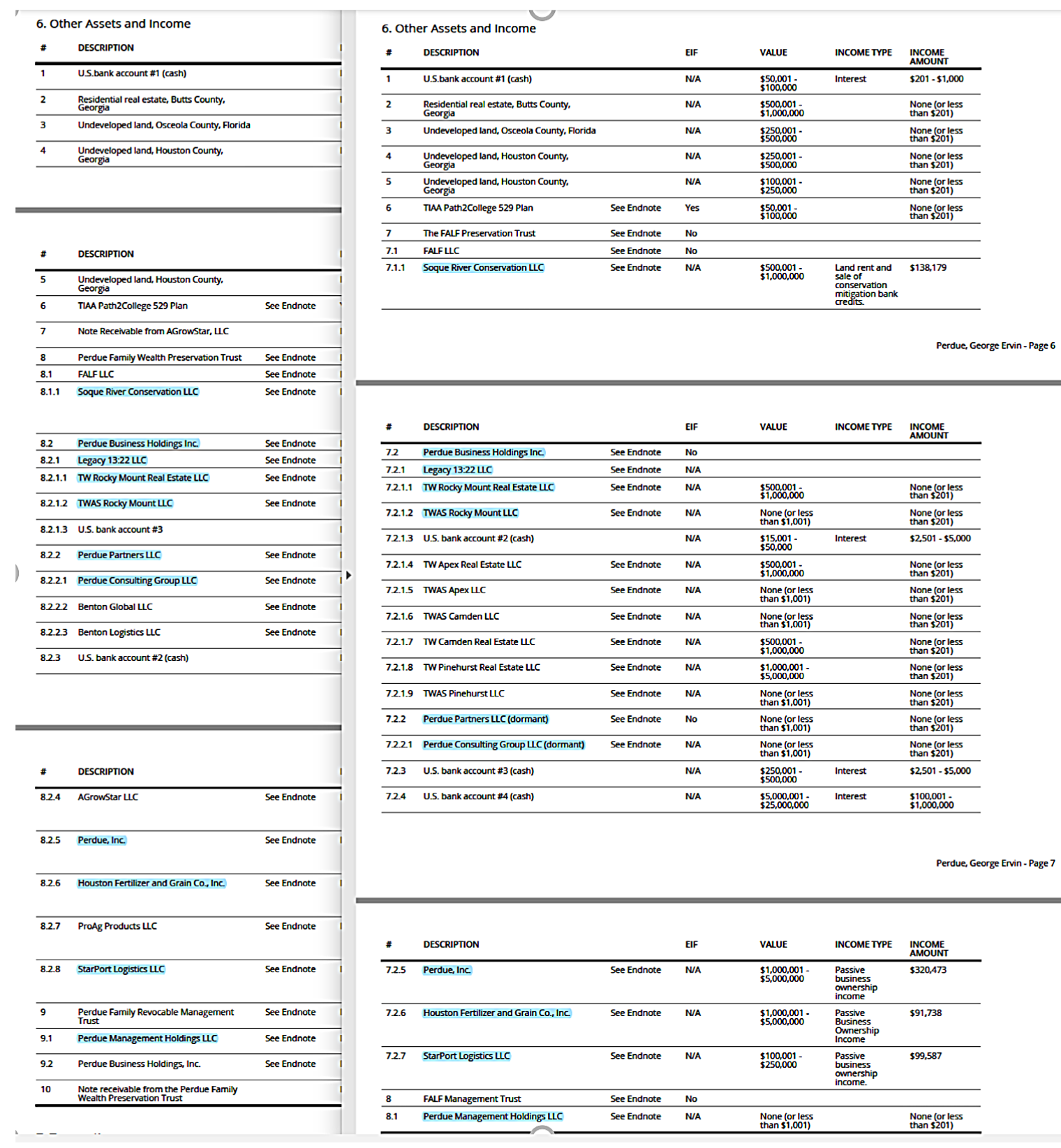

The two trusts were Perdue Family Revocable Management Trust and Perdue Family Wealth Preservation Trust. Of particular concern is a sub-entity called Perdue Business Holdings, which is the only sub-entity in the trusts specified in the ethics agreement. Let’s take a look at what assets were in those trusts in March 2017.

The trusts held multiple assets, most of which are held by Perdue Business Holdings (all assets that have numbers beginning with 8.2 are held by Perdue Business Holdings). Given that Perdue Business Holdings is singled out in the ethics agreement, and given the agreement’s requirement that the two trusts be restructured so they don’t benefit Perdue or his wife, none of the underlying assets in either trust should have benefited the Perdues after they divested.

On July 17, 2017, Perdue signed a certification saying that all steps outlined in his agreement had been taken. Perdue’s certification also makes a special note of Perdue Business Holdings — Perdue had to certify that he had transferred all financial interests in the sub-entity to a new trust for which he and his wife would not serve as trustees and from which they would not benefit.

Disappearing and Reappearing Assets

In 2018, when Perdue filed his annual ethics disclosure, he did not list either of the two trusts nor any of the assets that were held by the trusts, including Perdue Business Holdings.

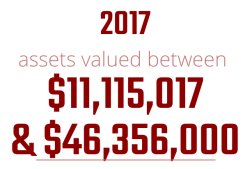

Perdue’s 2018 disclosure revealed other significant changes. Not only did the number of assets drop considerably; the value of Perdue’s assets dropped, too. In 2017, the assets he held were valued between $11,115,017 and $46,356,000, while in 2018 his assets were valued between $1,965,009 and $4 million.

In 2019, however, nearly all of the assets from which Perdue had divested, including Perdue Business Holdings, reappeared in two new trusts: the FALF Preservation Trust and the FALF Management Trust.

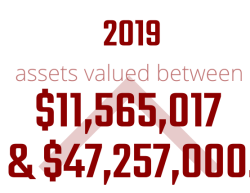

Not surprisingly, when Perdue’s assets reappeared in 2019, the total value of his disclosure increased to a level nearly identical to what it was in 2017: between $11,565,017 and $47,257,000.

In sum: Perdue agreed to forgo ownership of Perdue Business Holdings in 2017, disclosed in 2018 that he no longer owned Perdue Business Holdings or any of its underlying assets, then disclosed that he did, in fact, own Perdue Business Holdings assets again in 2019.

In sum: Perdue agreed to forgo ownership of Perdue Business Holdings in 2017, disclosed in 2018 that he no longer owned Perdue Business Holdings or any of its underlying assets, then disclosed that he did, in fact, own Perdue Business Holdings assets again in 2019.

There are some assets that had been part of Perdue Business Holdings in 2017 that did not reappear when that group of assets reappeared in Perdue’s two new trusts in 2019. It’s possible that the underlying conflict of interest was not with Perdue Business Holdings, but rather with one of the underlying assets that did not reappear in 2019, such as ProAg Products or AGrowStar LLC. Because Perdue’s ethics agreement does not detail why he had taken the steps he did, only that he had to take them, it was impossible for us to know whether Perdue was engaging in a conflict of interest that his ethics agreement sought to solve. What we do know is that by serving as a trustee of and benefiting from trusts that own Perdue Business Holdings assets, Perdue appeared to be violating the plain language of this ethics agreement, even if that violation would not otherwise be a violation of ethics rules or laws. This uncertainty also highlights the need for more transparency when it comes to disclosures.

Another question about Perdue’s ethics disclosures centered on transaction reports. In addition to annual disclosure forms, federal officials have to file a transaction report within 30 days of buying or selling a new asset. If the asset is bought or sold close to the time the official will file their annual disclosure form, there’s space to disclose their transactions there.

It appears that Perdue did not file a single transaction report after he was confirmed. When you search for all of Perdue’s ethics filings with OGE, there are only seven records. None of them are transaction reports. There aren’t any transactions listed in Perdue’s annual disclosure filings either. According to Perdue’s filings, as of January 13, 2021, he had neither bought nor sold any assets since his initial disclosure in 2017.

It appears that Perdue did not file a single transaction report after he was confirmed. When you search for all of Perdue’s ethics filings with OGE, there are only seven records. None of them are transaction reports. There aren’t any transactions listed in Perdue’s annual disclosure filings either. According to Perdue’s filings, as of January 13, 2021, he had neither bought nor sold any assets since his initial disclosure in 2017.

A Potential Explanation: Family Gifts

If we are to believe Perdue’s ethics filings, he gave away no less than $7.5 million worth of assets before the end of 2017, then around November 2018, those assets or nearly identical assets were returned to him through the FALF Management Trust and the FALF Wealth Preservation Trust.

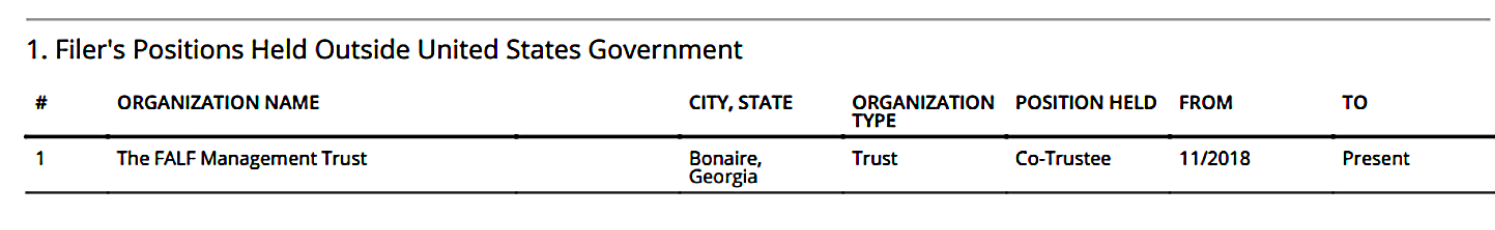

According to his 2019 disclosure, Perdue lists himself as a co-trustee of the FALF Management Trust, a position that apparently began in November 2018.

One way Perdue might have legally moved millions of dollars in assets out of, and then back into, his control without reporting any transactions centers on a loophole in the ethics guidelines for gifts to family members. Federal ethics rules do not require the disclosure of gifts of any value to or from relatives. Unlike other federal ethics rules that only apply to spouses and dependent children, the definition of “relative“ for the purposes of gift-giving is much broader and includes parents, siblings, adult children, and others. Gifts of any kind between family members, whether a birthday gift worth a hundred dollars or assets from a trust valued in the millions, are not required to be enumerated for federal ethics disclosures.

Given this loophole, Perdue could have gifted all of the assets from the original trusts to one or more of his family members such as his adult children. The family members could have then sold the offending underlying assets, and gifted the remaining assets back to Perdue through the new trust. Current ethics rules would not require any of those gifts or transactions to be disclosed because they would have transpired with Perdue’s non-spouse, adult relatives.

If the ethically problematic holdings were limited to ProAg Products and AGrowStar LLC (the assets that did not reappear in 2019) and not the other underlying assets of Perdue Business Holdings, this hypothetical could explain what happened with Perdue’s inconsistent financial disclosures. But because his ethics agreement does not specify which parts of Perdue Business Holdings were problematic, we cannot be sure.

Because of the limits of FOIA and privacy laws, there’s only so much American Oversight and other watchdogs can do to answer these questions. That’s why we called on USDA’s inspector general to investigate. Maybe Perdue has committed some serious ethics violations or maybe there’s a reasonable explanation. In either case, we hope that the inspector general takes a look and lets the American public know which it is.

In the meantime, American Oversight will continue to support greater transparency in federal ethics disclosures and to hold both current and former officials accountable to the American public.