The Scramble to Replace ERIC: How States That Left Nonpartisan System Have Fallen Short

The documents outlined in American Oversight’s far-reaching investigation show that states have scrambled to find viable replacements — none of which provide ERIC’s security, reliability, or effectiveness.

In 2023, as several states left the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC) in a bid to appease the far right election denial movement, they faced an obvious consequence of their hasty retreat from the data-sharing consortium: The lack of any solid plan to replace it.

Documents outlined in American Oversight’s new report “The Campaign to Dismantle ERIC” show that officials in the states that left ERIC, used to keep voter rolls up to date, hurried to replicate the benefits of membership, failed to adequately prepare election officials, and in several cases sought key information or worked on new programs well after they’d made the decision to withdraw.

Until last year, ERIC was a non-controversial nonprofit that quietly helped states securely compare voter data. In 2022, a group of 31 states and the District of Columbia were members of ERIC. But a political firestorm fanned by a coordinated effort on the part of anti-democratic activists led nine states to exit ERIC, a partnership that some of their leaders had previously touted.

Months after their withdrawals from ERIC, officials in Alabama and Virginia were working to obtain data that could help clean voter rolls. Alabama’s new secretary of state, Wes Allen, campaigned on a pledge to withdraw the state from ERIC and followed through by pulling Alabama out of the group immediately upon assuming office in January 2023. In March, the state’s director of elections emailed Amy Cohen, the executive director of the National Association of State Election Directors, asking how to obtain National Change of Address (NCOA) data — a critical component of voter roll list maintenance.

In August, three months after announcing its withdrawal, Virginia purchased the Limited Access Death Master File (LADMF), for $3,445. The LADMF contains data with the Social Security numbers of individuals whose deaths were reported — data that is accessible through ERIC. The next month, the state entered into a $28,960 contract to SysAudits for the sole purpose of auditing LADMF data compliance, underscoring the high cost of withdrawing from ERIC, which according to Votebeat cost about $40,000 in annual dues for 2019–2020.

Election authorities and experts in Missouri were also concerned about the lack of a clear plan for voter roll maintenance following the state’s exit in March. That month, the state’s Association of County Clerks and Election Authorities issued a statement calling on Missouri to “pursue an alternative resource” that would give local officials the necessary tools “to ensure secure, accurate, and efficient elections.” The records obtained by American Oversight reveal that guidance about Missouri’s plan for post-ERIC list maintenance was not provided to local authorities until June — nearly three months after its withdrawal.

The creation of new cross-state data-sharing agreements — an effort led in part by the Ohio secretary of state’s office — seems to have begun only after Ohio and Iowa had announced the suspension of their ERIC memberships, less than two weeks after Florida, Missouri, and West Virginia had done the same.

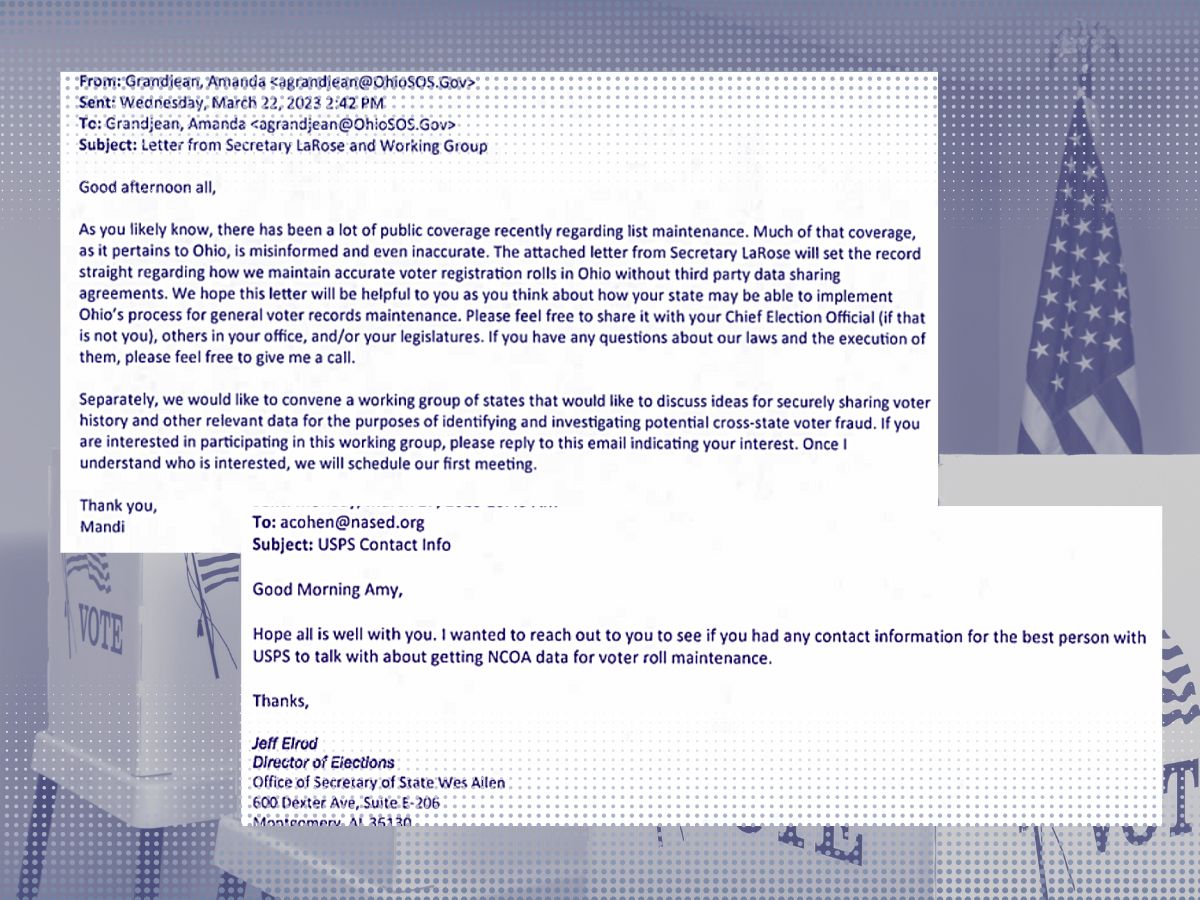

On March 22, 2023, Ohio Elections Director Amanda Grandjean sent an email to officials in several states, requesting the convening of a “working group of states that would like to discuss ideas for securely sharing voter history and other relevant data for the purposes of identifying and investigating potential cross-state voter fraud.”

The working group met regularly between March and June — after states had already left ERIC — to review potential data sources and discuss legal options for data-sharing agreements. And the working group’s emails from the spring of 2023 provide a glimpse into the complexities of devising viable alternatives to ERIC. Comments in the margins of a May draft memorandum of understanding for working group participants addressed a number of open questions with which states were grappling as they considered options, such as the legality of sharing confidential voter files, state rules about entering into data-sharing compacts, and how to manage information about potentially deceased voters.

Faced with having to maintain voter lists without the help of ERIC, states began turning to one-to-one data-sharing agreements with other states — but with each agreement subject to its own terms and security arrangements and without any common quality control. In June, Georgia and South Carolina signed the first of several interstate data-sharing agreements. Two months later, Georgia signed a similar agreement with Alabama.

Public reporting shows several other states have finalized such agreements. American Oversight also obtained a draft memorandum of understanding between Missouri and Florida, yet another link in the increasingly complicated web of interstate agreements aimed at replicating ERIC’s partnership.

Unlike ERIC, which was conceived in 2009 but not operable until 2012, the cross-state plans appear to have been designed in a matter of months — with a host of issues still to be worked out. The security and effectiveness of the quickly assembled patchwork of data-sharing agreements remains unclear.

Reporting by NPR in October 2023, which drew upon records obtained by American Oversight, noted the data-sharing agreements appeared to lack the kind of details that made ERIC reliable and effective. As one former county clerk in Utah told NPR, “These states have decided that instead of using a wheel, they’re going to invent a spherical device that will allow them to easily transport and roll items from A to B.”